We’ve come to the first of three VCS games published in the fall of 1979, and it’s a doozy. Superman is an incredibly ambitious game completely unlike anything seen up to this point on the VCS or its competitors; indeed, it’s an experience more in line with the games one would find specially made for computers. And what’s more, Superman absolutely succeeds in these ambitions: it’s a multiscreen adventure with a story, distinct goals the player has to achieve before they can reach an actual win state, and a conclusion to the tale and the game.

Superman is, as you’d expect, based off of the influential DC Comics character created back in 1938 by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. Superman is not the first licensed video game ever made – that honor goes to Fonz, a 1976 arcade game by Sega – but it is probably the first unique one, given that Fonz was just a rebranded version of Sega’s Road Race game. It’s also an early example of corporate synergy in the game industry. Warner owned both Atari and DC Comics at the time, and had just published the hugely successful Richard Donner Superman movie in December 1978. It wasn’t hard to find Superman merchandise aimed at kids from then through 1979, and according to developer John Dunn in a 2000 interview with Game Chambers, Warner had specifically put Atari up to the task of producing an accompanying game as soon as possible.

Atari’s marketing executives saw the proof-of-concept prototype that Warren Robinett had been developing for what would become Adventure while he was on vacation, and requested that he use that code as the basis for a VCS Superman title. Robinett learned of this during a programmers’ meeting after returning to the office, and it was a real good news/bad news deal. He now had the green light to continue work on his game, which his boss George Simcock had opposed and even reprimanded him for using time to create before Robinett left town for a month. On the flipside, these executives didn’t want Adventure as Robinett was pitching it, and while he indicated in several programmer meetings that he’d move away from his Dungeons & Dragons-inspired game if he had to, he really didn’t want to. Robinett continued developing the baseline code that any such expansive game would require regardless of theme, putting off committing one way or the other. After about four of these meetings, all of which included Robinett’s resistance to changing his concept, Dunn volunteered to take on the job of creating Superman – on the condition he could use a 4-kilobyte ROM chip on the cart. With the exceptions of Casino and Hangman, every game we’ve seen so far for the VCS has been written within two kilobytes – they were smaller games, but they were also cheaper to produce, and Atari was loathe to spend the extra money on 4k cart sizes to the point where the majority of game developers were not allowed to expand beyond 2k without specific permission. With pressure from Warner, manager George Simcock approved Dunn’s request, but given his art background and the concern he would go “artsy” and drag out development, Dunn was given a strict timeline to turn around a game. Robinett provided Dunn with the kernel – functionally a game engine – that he’d already made for Adventure to get him started, and Dunn set to work making the heavy modifications necessary to make his game.

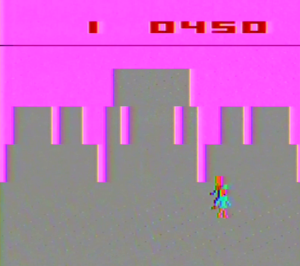

What Dunn ended up with is similar to the arguably better-known Adventure in enough ways that it’s clear they have the same starting point, but it’s also a distinct title in its own right that excels in areas that Robinett’s work falls short (and vice versa). In Superman, the player starts off as Superman’s alter ego Clark Kent on his way to work at the Daily Planet newspaper, when the villain Lex Luthor and his henchmen blow up the Metropolis Memorial Bridge and scatter. Ducking into a phone booth, the player then becomes Superman himself, with the task of tracking down the bridge pieces to rebuild it, capture Luthor and his henchmen and place them in the Metropolis jail, and then change back into Clark Kent in the phone booth and go to work at the Daily Planet. It’s a simple narrative, but at a time when any narrative was a rarity in video games, let alone a console game, this was quite a feat.

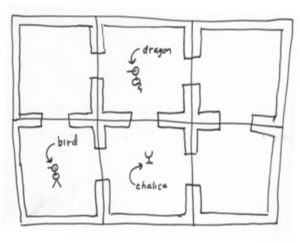

Playing as Superman allowed Dunn to utilize the character’s unique traits and abilities. With the ability to fly, players aren’t restricted to moving left-to-right in the game world – they can fly either up or down to skip ahead to another part of the game map. Pressing the controller button allows players to look ahead to the surrounding screens using his “x-ray vision,” a clever way to help players get the hang of moving around this new multiscreen adventure and find their targets. Before Superman, there weren’t any console video games with multiple screens for players to navigate to speak of outside of the flip-screen “scrolling” in Football for the Bally Arcade, and computers were expensive enough that few people actually owned them to play anything remotely similar. This was a new world for most players, and giving them a tool to see their surroundings was a wise design choice on Dunn’s part. The cacophony of sound that Dunn chose for the X-Ray vision deserves special notice, too – the soundscapes in early VCS games typically – though not always – tried to match up with real world sounds of vehicles or activities. But here is an early example of a game designer picking sound effects that really have no real-world counterpart. But it still “sounds” like x-ray vision, quite a feat with the VCS’s limited audio capabilities.

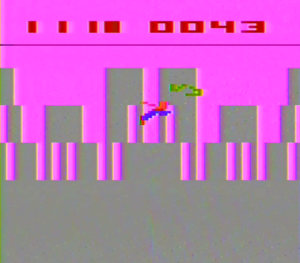

True to Superman’s weakness, Luthor and his crew have launched kryptonite satellites to depower the hero, leaving him unable to fly or able to pick up people or bridge pieces. These float throughout the world map, including when Superman is using his x-ray vision. To counter its effects, players throw DC Comics lore out the window and track down Lois Lane, Superman’s longtime love interest. Once you’ve touched her, Superman is back in action. The right difficulty switch adjust the speed of Luthor’s crew and the kryptonite satellites to make them faster or slower, while the left one adjusts whether or not Lois Lane comes to you when you’re depowered or if you have to track her down. Players can also pause the game by pressing the game select switch, a rare option on the VCS.

The game world features subway stations that Superman can enter to travel quickly around the city, including from the Daily Planet itself. Finally, there’s a helicopter. The helicopter flies around the game world, and will pick up bridge pieces and kryptonite satellites as it moves around – though functionally it doesn’t tend to make as big an impact on the game as you’d think, functioning effectively like the bat does in Adventure. In another nod to the comics, if the player has brought Lois Lane to the Daily Planet and the helicopter goes by outside, she’ll leave to go after it and try and get a scoop. For a 1979 video game, there’s a lot going on in Superman, and it honestly all hangs together. And true to the source material, Clark can’t actually die, only be slowed down. As such, the goal of the game is to simply complete it as quickly as possible. To that end, Dunn included a timer, functionally producing an early “speed running” game in the process.

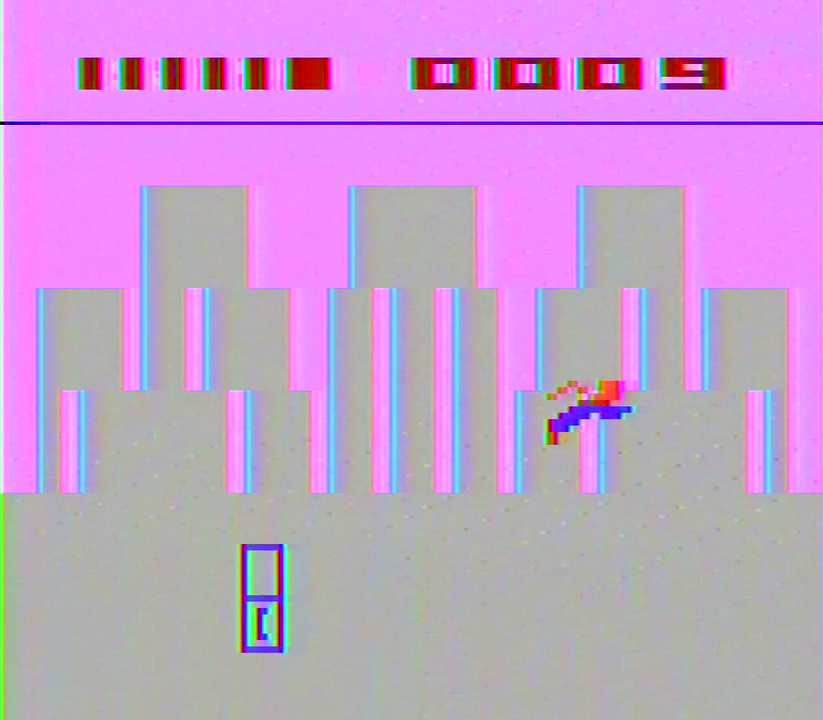

Dunn managed to infuse a lot of personality into the game, and his efforts paid off. Superman is not only an absolute classic on the platform, and Dunn brought a new level of refinement, artistry, and sheer inventiveness to the VCS. I would go so far to say that it’s probably still the best Superman game out there as of this writing. The on-screen indicators of the villains in the top left let you know how many are left to capture and take to the jail, and while there’s no such indicator for the bridge pieces, the fact that there’s only three of them makes it pretty simple to figure out – once you’ve dropped all three pieces on the bridge screen they’ll automatically assemble. Navigating the map takes a little getting used to, as it doesn’t line up into a proper square, but the x-ray vision helps. More awkward is Superman’s tendency to fall when you’re flying if you stop moving – which in a sense is in keeping with his original skillset of just being able to jump really high – and if you let him touch down while he’s carrying someone or something, he’ll let go – meaning Luthor and his crew can try to get away. You can fortunately hold him in the air by holding down the button on the controller, which puts him into X-ray vision mode. The game does suffer from some pretty heavy flicker when multiple objects are on screen (probably as a holdover from the Adventure kernel, another flickery game), but honestly these are minor gripes. The game plays well once you get the hang of it, and probably owing to Dunn’s artistic background, Superman looks great. This is easily the prettiest VCS game to date, with a 21-screen cityscape that is – for using low-resolution background graphics – rather distinctive. The higher resolution elements, such as the phone booth, bridge, subway entrances, jail, and Daily Planet logo are all recognizable. The human characters are where the game really shines, however. The rare occasions we’ve seen VCS developers draw human characters they’ve all been one color, as that’s much easier for the system to render. But here, every character is brightly colored with their own clothing and accoutrements, from Luthor’s helicopter backpack to the hats Clark Kent and the rest of the cast wear, to the little tommy guns Luthor’s men carry around. Superman may not have hair, but considering he has his distinctive blue and red costume, he’s already head and shoulders more sophisticated than anyone else to come before him on the platform. And there are cute moments of animation, such as Lois Lane’s leg kick when she touches Superman, which is designed to suggest a kiss. Dunn didn’t include a black-and-white mode, but admittedly the game relies on color for navigation, particularly within the 5-screen subway system, so it’s possible he just didn’t have the time to make it work in grayscale.

Once you’ve gotten the hang of the game, you can complete it quickly on the basic difficulty level – especially if you’ve got the world map handy. Until you’ve gotten a sense for how each screen connects to the others, navigating the city can get tricky owing to its odd shape. The options provided by the difficulty switches expand the game’s length by making you work harder to catch your foes and stay powered up, but ultimately you’re still rushing through in a matter of minutes. Interestingly, there are tricks that allow you to keep the bridge intact and leave you to just catch the villains, or even to skip straight to the Daily Planet and finish the game within seconds. Dunn said of the latter one that he hadn’t planned that trick in the game but found it during development; thinking it was cool he just left it in. Even today speedruns for the game have to specify whether or not any of these tricks will be used.

If there is any weakness to Dunn’s game, it’s the two-player cooperative mode. In this game type, one player controls Superman’s vertical movement and the other his horizontal. Dunn said simply that it sucked, and that he wished he’d had the time to make a proper cooperative mode – likely with the second player controlling Lois and giving her more to do. While this does mean he produced an early, if awkward, example of a co-op game, I can’t help but wonder how an asymmetrical cooperative game like he had thought about would have turned out, and what kind of influence that could have had.

Contemporary reporting sings the praises of the game. Superman leads off an Arcade Alley column in the April 1980 Video magazine, where authors Bill Kunkel and Arnie Katz declared there were no video games remotely similar to it. They further refer to it as assured for a Video Arcade Hall of Fame spot while also asking for more games in the same vein. Indeed, they gave it Game of the Year in the first issue of Electronic Games, referring to it as the most important release of 1980 – illustrating that with few exceptions games didn’t really drop on specific dates in this era, but rather just trickled out to stores over time. Video Action saw a three-page overview of the game by comic book writer Paul Kupperberg in its inaugural issue, where he remarked the game had complex and imaginative action that made it one of the most challenging and best games on the market before spending the rest of the piece explaining just how it plays. This also features an early reference to “speedrunning,” where Kupperberg talks about trying to shave your time down with each playthrough. The September 1980 Space Gamer issue reviewed both Superman and Adventure, and the reviewer, Norman Howe, heaped much of his praise on the former, considering it more interesting and complex than Adventure and the best Atari game on the market. Videogaming Illustrated also gave it the runner-up for best game based on a non-arcade medium, losing only to Parker Brothers’ blockbuster hit, Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back. Amusingly, Superman came up as one of the best console games in a Joystik feature talking with arcade developers about their favorite home games – Vid Kidz co-founders Eugene Jarvis and Larry DeMar highlighted it, with DeMar taking it a step further and calling it the best thing Atari had ever done. Jumping ahead nearly 20 years after its debut, Joe Santulli reminisced about Superman in the pages of his zine Digital Press, considering it a groundbreaking hit far removed from Atari’s early releases, adding that it’s truly difficult to put into perspective just how big a shift it was from the traditional points- and wave-based games that were available before.

While it’s hard to get a fix on the game’s sales, it was heavily promoted in print ads early on – even including a campaign for a free Superman wallet offer – and got a new lease on life when Superman II hit American theaters in 1981. It continued to be advertised in Atari catalogs through 1983, though it finally vanishes from the 1984 catalog. The game doesn’t appear to have been sold in the Atari Corporation years, but this isn’t surprising. The company had spun off of Warner and likely no longer had the rights to continue to publish Superman as a result. It did appear to still be appreciated critically and commercially into 1982, when Videogaming Illustrated printed a strategy guide to the game.

Superman does seem to be the first of a few VCS games to get delayed. Initially the game was advertised in trade magazines to come out in the summer, but the earliest newspaper advertisements I’ve found for it don’t come out until September. With delays also hitting Video Chess and Basic Programming – the latter pushed back all the way into 1980 – it’s possible that Atari either had issues producing enough 4k sized cartridges or was still getting a handle on new game releases coming year-round instead of just every fall. Either way Superman doesn’t seem to have been impacted too badly – probably because it was such a high profile game. That said, it’s a little unclear just how well Superman sold, as only 23 titles are visible in the glimpse of an internal Atari sales tracking memo seen in Once Upon Atari, and none of them feature Ma Kent’s baby boy. All we can say is that it did not sell more than 1.4 million copies (the amount Centipede sold, and the only real benchmark we have for the bottom half of the list). That said, with Superman-mania in full force following the 1978 movie, we can surmise it probably did pretty comfortable numbers.

This would be Dunn’s sole VCS release to actually reach store shelves. Prior to Superman he said he worked on a game called Snark, which he described as a maze game where players would have to shoot monsters as they navigate their way through a randomly generated labyrinth. Snark went unpublished due to intense color cycling, and concerns within the company that it could cause seizures. A prototype of Snark turned up in 2022, quite similar to how Dunn had described it in his interview. Here, you control a tank of sorts trying to shoot a block known as the Snark as it travels around the maze; hitting it earns you 3 points, with the first player to reach 21 points winning the game in two-player modes (single player game modes replace the 2nd player with a constantly moving computer-controlled bullet). Touching the Snark itself costs you 5 points, however, and you lose points by shooting your opponent instead of the Snark as well. The targeting controls are particularly unusual, since you have to hold down the button to aim your shot before letting go of the joystick itself to fire, and bullets bounce around akin to Tank-Pong from Combat… moreover, you only have the one bullet, which only returns to you when it either hits the Snark, your opponent, or you catch it. There is a second maze accessible through very specific conditions: you need to shoot or touch the Snark at the same time the screen is flashing due to the opponent doing the same. But the “intense color cycling” Dunn mentioned in his interview comes up in game types 5-8, where the background is constantly changing colors; it doesn’t seem to actually have any other gameplay changes other than making the screen harder to parse and possibly and unintentionally cause seizures. It’s a clever game, but understandable why it was shelved given the video spin modes in those latter game types. Even as someone without epilepsy, it actively hurts to watch the game screen for more than a few seconds at a time. The targeting controls are also incredibly funky and hard to parse; Dunn’s second cartridge attempt with Superman is such a dramatic improvement upon Snark that it may be for the best that this one never made it out the door.

And after Superman Dunn tried to push management to produce more games with, as he called them, positive subliminal messages – for example, a Dungeons and Dragons game where challenging the dragon to a puzzle would get a better result than just fighting it. This was a forward-thinking piece of game design that Superman alludes to, but one that management didn’t go for on a more focused level; Dunn left the company with the intention of making such games independently, but ended up finding the graphics editor was more interesting than the game he was working on anyway, ultimately publishing it as the paint program Slidemaster. Dunn passed away in 2018, after a career working on algorithmic music and art programs; I must thank the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine for saving his in-depth Game Chambers interview with Randy Ball long after the website went offline.

While not every game coming down the VCS pipeline will be quite as impressive as Superman, it’s hard to imagine that titles like Haunted House, Pitfall! or Fathom would have come together quite as they did in a world without Superman – or Adventure, due to Robinett’s base-level coding. And as for Adventure, Robinett’s game would be published in 1980, and is rightly considered a hugely influential title that is unquestionably better remembered today. But Superman was a big deal at its own release, and set the market expectation for more advanced games that allowed developers to work with bigger and bigger game sizes on more ambitious projects. Following Superman, 4k cartridges quickly became the new standard for Atari’s VCS releases, as the company phased out new 2k games in favor of the additional space. Superman also frankly does some things better than Adventure, notably in terms of recognizably human characters and a narrative structure. So while its sibling may get more accolades today, Atari’s Superman remains one of the gems of the VCS library. It’s without question the standout game on the platform from its first three years on the market, and a bright sign of things to come.

Sources:

John Dunn, interview with Randy Ball, Gamechambers.com, 2000

Snark, Atariprotos.com

Arcade Alley, Video, April 1980

Electronic Games, Winter 1981

Making the Dragon, Warren Robinett, 2021 version (unpublished as of this writing)

Videogaming illustrated, August 1982; April 1983

Space Gamer, September 1980

Video Action, December 1980

Joystik, November 1982

Random Review: Superman, Digital Press, May 1998

Release date sources:

Superman, September 1979 – Source: Honolulu Star Bulletin, September 13 1979; Honolulu Star Bulletin, September 27 1979; Washington Post, October 19 1979; Frankfort Star, December 2 1979; Merchandising, June 1979; The Herald News, November 21 1979

Adventure, March 1980 – Source: Chicago Tribune, March 23 1980; Washington Post, March 28 1980; Honolulu Star Bulletin, April 3 1980; Plain Dealer, April 9 1980

1 thought on “Superman – September 1979”