We’ve seen a slow progression of video game sports through the 1970s up to this point, both on the VCS and off of it. Pong was a deeply simplified version of ping pong, and all the other sports games on the original Magnavox Odyssey were functionally the same basic thing. The same holds true for a number of early arcade sports renditions: hockey becomes Pong with a specific goal area, Volleyball and Basketball become vertically oriented versions of Pong, and so on. Racing games got to become their own genre pretty early on, however, and baseball followed shortly thereafter. 1978 would prove to be a watershed moment for one particular sport, however, as a full, non-Pong version of Basketball made its debut on the Atari VCS.

Coincidentally release at the same time as another basketball game that came out alongside the Magnavox Odyssey2 in 1978, Atari’s VCS version of the sport is seemingly the first commercial attempt at the game to really try and translate the major appeal of basketball into a video game. Creator Alan Miller has noted that he played on his high school basketball team, and as the eldest of six kids had spent a lot of time in his youth coming up with games for everyone to play; it seems likely that he wanted to try and translate a sport he enjoyed to the VCS, and he largely succeeded.

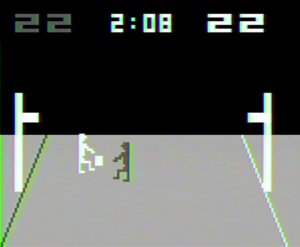

“I wanted to do a game that used moving player objects,” Miller told Electronic Games in July 1982 interview. His previous games – including Surround, Hangman and Hunt And Score, were all largely based around using low-resolution background graphics, and here with Basketball was Miller’s first attempt to make good use of mobile player sprites. Miller opted not to attempt a team version of basketball, instead bringing it down to a one-on-one competition. Each player starts out at the center line vying for the jump ball; once someone scores, the previous defender will take the ball from under the net while the scorer is set back to the center line to try and defend. To avoid stalling tactics, players can’t cross or dribble the ball outside of the court endlines, and the game clock only lasts for 4 minutes before the competition concludes.

“I wanted to do a game that used moving player objects,” Miller told Electronic Games in July 1982 interview. His previous games – including Surround, Hangman and Hunt And Score, were all largely based around using low-resolution background graphics, and here with Basketball was Miller’s first attempt to make good use of mobile player sprites. Miller opted not to attempt a team version of basketball, instead bringing it down to a one-on-one competition. Each player starts out at the center line vying for the jump ball; once someone scores, the previous defender will take the ball from under the net while the scorer is set back to the center line to try and defend. To avoid stalling tactics, players can’t cross or dribble the ball outside of the court endlines, and the game clock only lasts for 4 minutes before the competition concludes.

Not only is this among the first basketball video games to actually make a real attempt at depicting the sport accurately, it’s the first one to use an angled three quarters forced perspective viewpoint, which would become the standard for a great deal of basketball games going forward. In a fall 1983 Creative Computing Video & Arcade Games interview, Miller explained that he really enjoyed working out the perspective side of Basketball’s design, though he noted it wasn’t perfect – after the game came out, he got feedback from players finding it difficult to follow the ball’s movement without some kind of shadow.

The joystick allows each player to move around the basketball court, with the defender always facing the ball. To shoot, the player with the ball pushes in the button, causing their character to stop moving and begin waving the ball above their head; depending on where their character is in their animation cycle when the button is released, the ball could fly high and long or low and fast. Regardless of where you are vertically on the playfield, the ball will always go right towards the hoop, and the perspective is odd enough that as long as it lines up with the net it’ll likely pop in. The defender can push their button to jump and try and block the shot, though only when the ball is in its upward arc. You can also steal the ball by lining up the two basketball players and running past as the ball is being dribbled. There’s no goaltending, no three-pointers, no fouls, just dribbling the ball, stealing, and shooting. That’s basically all there is to the controls; the difficulty switches will adjust the individual player’s movement speed, but there aren’t a bunch of variations to get a handle on. Well, save a very important one.

The joystick allows each player to move around the basketball court, with the defender always facing the ball. To shoot, the player with the ball pushes in the button, causing their character to stop moving and begin waving the ball above their head; depending on where their character is in their animation cycle when the button is released, the ball could fly high and long or low and fast. Regardless of where you are vertically on the playfield, the ball will always go right towards the hoop, and the perspective is odd enough that as long as it lines up with the net it’ll likely pop in. The defender can push their button to jump and try and block the shot, though only when the ball is in its upward arc. You can also steal the ball by lining up the two basketball players and running past as the ball is being dribbled. There’s no goaltending, no three-pointers, no fouls, just dribbling the ball, stealing, and shooting. That’s basically all there is to the controls; the difficulty switches will adjust the individual player’s movement speed, but there aren’t a bunch of variations to get a handle on. Well, save a very important one.

Basketball is notable for its inclusion of a computer opponent, which was certainly not a guarantee for sports video games at the time. Furthermore, it’s a pretty good computer opponent that will play more aggressively the closer the score is. Th computer is incredibly difficult to beat, as it does a good job of being right in your face to steal or block the ball, and it rarely misses its shots. It provides an impressive challenge, especially if the human player has flipped the difficulty switch to move more slowly – which I can really only recommend if you’re extremely good at this game. Like many early VCS games, when you have two human players Basketball shines. It’s a fast game, and the adjustable character speed is an admirable way to get the handicapping to work effectively. But for those times you don’t have a second player available Miller provided a good challenger to face off with.

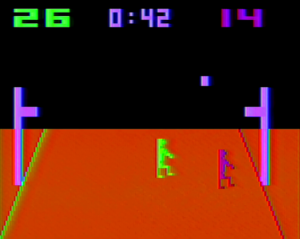

As previously mentioned, Magnavox’s Odyssey2 Basketball cart came out about the same time as the Atari version, and it provides a helpful contrast into why Miller’s cart is so much more effective. Like Miller’s game, the Magnavox version written by Sam Overton is a one-on-one affair, but it lacks the nuances of the Atari VCS game. When the ball is being shot, there is no way to actually control its arc – rather, it is entirely random, and could just as easily bounce back into the playfield. This playfield, incidentally, is not the same three quarters forced perspective of the VCS game, but a simple side view that limits its two human players to sliding left and right. There’s no dribbling or stealing the ball; just get in the way of the opponent’s shot to get the ball, or grab it on the rebound. This Odyssey2 release feels like a half-step between the Pong-style basketball games that preceded it, and is far less sophisticated than what Atari was selling at the same time it debuted.

Atari’s Basketball was well received. Over in Video Magazine, the game was reviewed as part of a broader VCS piece in the summer 1979 issue, where authors Bill Kunkel and Arnie Katz praised the pacing of the game and noted that the computer was a tough opponent when scores got tight. Most prestigiously, the game won the Most Innovative award in the first ever Arkie Awards that Kunkel and Katz gave out in March 1980’s Video edition. The duo wrote that Basketball won it for featuring the third dimension on the court, which allowed players to move up and down as well as back and forth. This, coupled with the computer opponent and defensive shot blocking, sealed the deal. Praise for the game extended outside of the pages of Video, too. The Xenia Daily Gazette out of Ohio ran a review by Dick Cowan on February 24, 1979 specifically about Basketball and Outlaw. Cowan raved about Miller’s sports game, calling it one of the very best games any manufacturer had put out; he brought special attention to the defensive play and referred to stealing the ball or simply freezing out your opponent by keeping the ball away as the timer ticks down as being realistic to the sport. A February 1, 1979 article running in Madison, Wisconsin newspaper the Capital Times quotes a local Sears electronic games expert as saying that Basketball was the most popular VCS game they had. It also preceded two more basketball games from Atari that played quite similarly: in 1979, an arcade basketball game was published by the company, while another basketball title written by Miller for the Atari 8-bit computer line launched for the Christmas season that year alongside the computers themselves. Effectively a conversion of his VCS title, this would be his final game with Atari before leaving the company, as he would be sucked into the effort to finish up the computer operating system alongside several other star programmers before leaving to found Activision in August 1979.

And credit to Miller, as not only was his original hoops game well-liked, but it ended up being one of the only takes on basketball the VCS saw for the bulk of the console’s market life. A two-on-two version of the game, titled Realsports Basketball, was in development in 1983, but ended up canceled because the game wasn’t coming together particularly well; the prototype that has leaked out looks marginally better than Miller’s 1978 game but doesn’t play as well, with simplified ball stealing and less nuance to the mechanics of

basketball in general. Atari did manage to release a second basketball game, Double Dunk, around May 1989 that brought a two-on-two, half court version of the game to its aging workhorse. Whoever isn’t controlled by the players becomes computer controlled, and the game features options to adjust the length of the game, shot clocks, three pointers, lane violations, and fouls. It’s a robust game; though while it is clearly more advanced than Miller’s original game, it also plays rather differently just as a matter of having more players and a different viewpoint. And even after Double Dunk came out, Atari continued selling the original Basketball cart – between 1986 and 1990, about 91,000 copies of the game were sold. Miller himself would use the perspective lessons he learned making Basketball to refine his next VCS sports game, Tennis. Learning from the common complaint he received about Basketball and the difficulty in discerning the ball’s position relative to the hoop, Miller ensured that the ball in Tennis featured a shadow to make it clear. This change was well received, though in Basketball’s case, the game is quick enough that by the time a player can get annoyed over a whiffed shot the ball is likely already on its way to one hoop or another.

More realistic takes on basketball would follow, notably with Mattel’s NBA Basketball for the Intellivision, but the fast and loose “arcade-style” approach at the game would prove durable. Titles such as NBA Jam may not have been directly influenced by Miller’s early VCS title, but their DNA can be traced back to the rendition of the game he put together here. The VCS struggled somewhat with its non-racing sports games early on, but Basketball nails the shot and proves to be one of the system’s more enduring – albeit lesser known – titles.

Sources:

Electronic Games, July 1982

Creative Computing Video & Arcade Games, Fall 1983

Computer Gaming World, November 1986

They Create Worlds, Alex Smith, 2019

Merchandising, March 1980

Video, Summer 1979, March 1980

Madison Capital Times, February 1 1979

Xenia Gazette, February 24 1979

Alan Miller, interview with Al Backiel, 2003