the release of the Atari keyboard controllers in the fall of 1978 necessitated the development of games that actually use them. Atari’s developers were in need of game ideas that could play to the keyboards’ strengths, and as such turned primarily to existing mental puzzles and computer programs. We saw this last time with Larry Kaplan’s Brain Games, a collection of basic memory and mathematic games, and we’ll see it again next time with Hunt & Score. But for now, we’ve got Codebreaker, which is the VCS rendition of a pair of logic puzzle games with fuzzy origins; one dates back at least to the early 1900s and the other to around the 1500s in its current form, but is probably really a variant of a number game that goes back to the earliest days of human civilization.

The original version of the first game on this cart is known as Bulls and Cows for reasons I haven’t quite managed to put together. In that rendition, one player comes up with a secret, four-digit number and the other must try and guess it in as few turns as possible. After the second player gives their guess, the first player lets them know how close it is by telling them the number of cows – the number of digits that are correct but in the wrong position – and the number of bulls – the number of correct digits in the right spot. If the second player gets four bulls, they win the game. The game is probably better known under the name Mastermind, a codebreaking game using colored pegs instead of numbers that was first published commercially in 1971 by Invicta Games.

As a game that relies on numbers and has very few, if any, graphical elements, Bulls and Cows was well-suited to early computer systems. The first known conversion of the game to a digital format is 1968’s MOO program, designed by Frank King for Cambridge University’s Titan mainframe, where it proved to be popular enough that restrictions needed to be put in place so that the game didn’t suck up all the machine’s resources. The program found its way to other university mainframe systems in the following years, and gained wider notoriety thanks to an article titled Computer Recreations in the April-June 1971 edition of the Software, Practice and Experience journal. The game would be further popularized among computer enthusiasts when David Ahl included it under the name Bagels in his 101 BASIC Computer Games book, first published in 1973. Mastermind even got a handheld electronic version by Invicta Games in 1979 before the fad ran its course. Needless to say, it was a good candidate for early video game consoles, as Moo would find its way to the VCS and several of its early competitors.

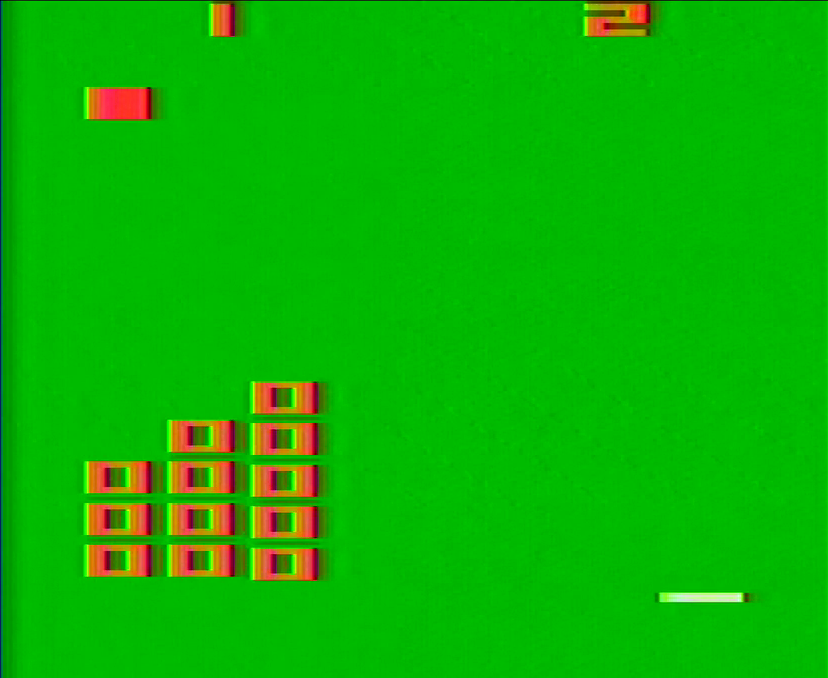

For the VCS version, dubbed Code Breaker, either the computer or a second player comes up with a secret code that needs to be guessed. This can be either a three digit or four digit code, with a numerical range of one through six or one through nine. If it’s a one player guessing game, then the player has either eight or 12 guesses – depending on the difficulty switch arrangement – to determine the right code sequence; the score is based on how few guesses it took to get the right answer.

For the VCS version, dubbed Code Breaker, either the computer or a second player comes up with a secret code that needs to be guessed. This can be either a three digit or four digit code, with a numerical range of one through six or one through nine. If it’s a one player guessing game, then the player has either eight or 12 guesses – depending on the difficulty switch arrangement – to determine the right code sequence; the score is based on how few guesses it took to get the right answer.

Since there are two different versions of the two-player game – with the second player either coming up with the code or guessing it as well – there are, accordingly, two different scoring methods. In the variants where two players are guessing together, they will take turns entering in their guesses, with a point awarded only to the person who gets the answer right. If a player is entering in the code, then play alternates after each successful answer, with scoring being based on the fewest number of guesses needed.

The game makes the guessing information readily apparent on the screen and easy to parse. After entering in your guess, the game will provide you with a series of white and black marks. A white line represents the cows, and tells you if you have a right digit but in the wrong place, while a black line represents a bull – meaning you have a right digit in the right place. Like in the original game, there’s no indication which number is correct – you just have to narrow that down yourself. Horizontal dashes on the bottom right side of the screen tell you whose turn it is in two-player games, while the keypad handily allows you to enter digits by simply typing them in and pushing the number sign key (or hashtag for the younger crowd).

This is really a game you need to concentrate on, and is easier to succeed at if you’re actually working cooperatively with your opponent to some extent. While the game keeps track of all the guesses (until they scroll off screen, more of an issue in a two player setting), it’s up to the players to try and reason out what numbers can be eliminated and which are the likely culprit, and if you’re not paying attention or trying to rush your thought process, you’re going to find yourself flailing until you run out of turns. I enjoyed it, but it is completely unlike anything else on the VCS.

This is really a game you need to concentrate on, and is easier to succeed at if you’re actually working cooperatively with your opponent to some extent. While the game keeps track of all the guesses (until they scroll off screen, more of an issue in a two player setting), it’s up to the players to try and reason out what numbers can be eliminated and which are the likely culprit, and if you’re not paying attention or trying to rush your thought process, you’re going to find yourself flailing until you run out of turns. I enjoyed it, but it is completely unlike anything else on the VCS.

The other game on the Codebreaker cart is a rendition of Nim, a math game known to be a few centuries old that is related to the ancient – and still quite popular – game of Mancala. Like Bulls and Cows, Nim was well suited to early computers and electronic gaming devices, including the Nimatron machine displayed at the New York World’s Fair in 1940 and the Nimrod computer showcased at the Festival of Britain in 1951. The idea behind this game is that you have one to four stacks of objects; the two players – one of which can be the computer in this version – alternate removing objects. You can pull as many objects as you want, but only from one stack at a time; depending on the gametype you win either by removing the last object or by forcing your opponent to remove the last object.

The VCS version gives players a couple options for setting up the game; either the computer will do it by setting up three stacks consisting of three, four and five objects, or the player can customize their own Nim game with between one and four stacks consisting of up to nine objects. The asterisk key represents your cursor, allowing the player to move from stack to stack; when setting up a game you simply push the key for the number of objects you want in the stack and then move on until you’re done, at which point you can just push the number sign key to finish.

When you’re actually playing the game, the asterisk again moves you from stack to stack, and the keypad’s numbers indicate how many objects you plan on pulling from that stack. Once you’ve put in your moves, you can push the number sign key to finish your turn. And that’s about it. You can flip the difficulty switch to make your computer opponent a better player, but otherwise you’re just trying to outwit your opponent.

Nim is an incredibly simple game, but owing to its longevity it’s also a fun one. Games go quickly, and in true VCS fashion it especially shines against a human opponent. One could make the argument that you don’t need a home console to play Nim – or Codebreaker – as long as you have some items around the house to use instead, but the Atari system is certainly a good way to do it if you don’t have another person on hand.

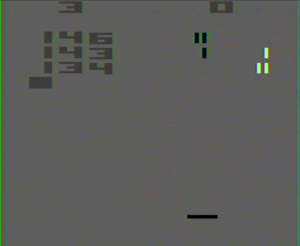

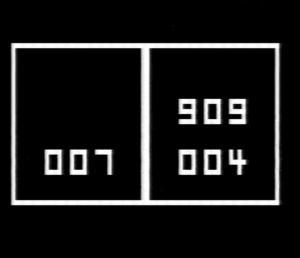

Bulls and Cows shows up on the RCA Studio II cartridge Fun with Numbers, which features both single and two-player modes. This version of the game gives you 20 guesses to figure out what the three-digit code number is,  which seems generous, though the clue system is needlessly elaborate – possibly as a way to make things more difficult. Instead of using colored lines as an indicator (since the system uses black-and-white graphics) the game instead has a three digit “computer clue.” Three zeroes means that no digits are correct, while zero zero one means the same thing as a cow – one digit is correct but in the wrong place. Zero zero two means you have one digit correct and in the right place, or more confusingly, two digits are right but in the wrong place. Numbers three through five are any feasible combination of the previous options, save for the one with three zeroes; each of the numbers indicates a point for being “correct,” which seems confusing enough that the manual gives you an explanation. Essentially if the secret number is 3-4-5 and you entered 3-3-3, you would get 004 as a hint because you get two points for the first 3 being in the right place and two additional points for the other two 3s for being correct digits in the wrong place. If you get zero zero six and a beeping tone, you guessed the number correctly. The two-player mode has each player come up with their own code number and alternate turns to see who can guess their opponent’s first. It’s a reasonably good take on Bulls and Cows, and certainly plays to the Studio II’s strengths.

which seems generous, though the clue system is needlessly elaborate – possibly as a way to make things more difficult. Instead of using colored lines as an indicator (since the system uses black-and-white graphics) the game instead has a three digit “computer clue.” Three zeroes means that no digits are correct, while zero zero one means the same thing as a cow – one digit is correct but in the wrong place. Zero zero two means you have one digit correct and in the right place, or more confusingly, two digits are right but in the wrong place. Numbers three through five are any feasible combination of the previous options, save for the one with three zeroes; each of the numbers indicates a point for being “correct,” which seems confusing enough that the manual gives you an explanation. Essentially if the secret number is 3-4-5 and you entered 3-3-3, you would get 004 as a hint because you get two points for the first 3 being in the right place and two additional points for the other two 3s for being correct digits in the wrong place. If you get zero zero six and a beeping tone, you guessed the number correctly. The two-player mode has each player come up with their own code number and alternate turns to see who can guess their opponent’s first. It’s a reasonably good take on Bulls and Cows, and certainly plays to the Studio II’s strengths.

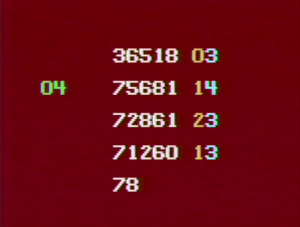

Bulls and Cows also appears on the Odyssey2 cart Matchmaker! Logix! Buzzword! as the titular Logix game. The Odyssey2 gives the player a five digit code to guess. After a guess, a two digit number to the right of the guess provides the number of correctly placed digits on the left, and the number of correct digits on the right. This still has the object of answering in the fewest guesses, but there are no limitations on how many times you can guess. Unlike the Studio II version, numbers in the code are thankfully always unique – no doubling up on your twos and threes here. Helpfully, the Odyssey2 version allows for the use of the keyboard for entry rather than relying on a hand controller, as the final version of the game we look at does. Much like the Studio II, this title plays to the Odyssey2’s strengths, though the lack of options does leave it a little threadbare.

Bulls and Cows also appears on the Odyssey2 cart Matchmaker! Logix! Buzzword! as the titular Logix game. The Odyssey2 gives the player a five digit code to guess. After a guess, a two digit number to the right of the guess provides the number of correctly placed digits on the left, and the number of correct digits on the right. This still has the object of answering in the fewest guesses, but there are no limitations on how many times you can guess. Unlike the Studio II version, numbers in the code are thankfully always unique – no doubling up on your twos and threes here. Helpfully, the Odyssey2 version allows for the use of the keyboard for entry rather than relying on a hand controller, as the final version of the game we look at does. Much like the Studio II, this title plays to the Odyssey2’s strengths, though the lack of options does leave it a little threadbare.

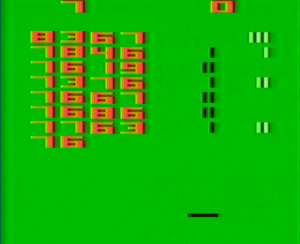

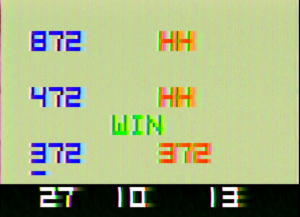

The only other game console to host Nim or Bulls and Cows is the Fairchild Channel F, with its cartridge Magic Numbers. Mind Reader, Fairchild’s take on Bulls and Cows, gives players the option to guess a code somewhere  between 2 and 5 digits, with the further option of guessing within 20 turns or a time limit. Since the Channel F doesn’t have a keypad, the player has to move the cursor between digits by pushing the control knob left and right, and cycle through numbers by twisting the knob left or right; pushing down locks in your guess. For this version, it uses the letters H and T to indicate bulls and cows, respectively – the letters stand for Hit and Transpose. Nim is also on the cart, and allows the player to choose between 3, 6 and 9 stacks and whether or not they want a time limit; each victory earns the player or the computer points, with the first to get 100 points winning the overall session. These are decent takes on these games, but the lack of two-player option does hurt them. The computer is also an incredibly brutal Nim opponent, to the point that the instruction manual even includes a section with hints on how to win.

between 2 and 5 digits, with the further option of guessing within 20 turns or a time limit. Since the Channel F doesn’t have a keypad, the player has to move the cursor between digits by pushing the control knob left and right, and cycle through numbers by twisting the knob left or right; pushing down locks in your guess. For this version, it uses the letters H and T to indicate bulls and cows, respectively – the letters stand for Hit and Transpose. Nim is also on the cart, and allows the player to choose between 3, 6 and 9 stacks and whether or not they want a time limit; each victory earns the player or the computer points, with the first to get 100 points winning the overall session. These are decent takes on these games, but the lack of two-player option does hurt them. The computer is also an incredibly brutal Nim opponent, to the point that the instruction manual even includes a section with hints on how to win.

Codebreaker, initially announced early in 1978, appears to have been made available in October alongside the other two keypad controller games, with a release the following May in the United Kingdom. The game, coupled with fellow inaugural keypad title Hunt & Score, would be bundled with a free pair of keyboard controllers in a deal that ran from June through September 1980 – whether this was to try and move more keyboard products or not, it helped keep Codebreaker in circulation. The game continued to appear in Atari catalogs through 1982; its absence beyond that point leaves me wondering if it continued to stay in circulation into 1983 or if it was simply deemed not worth advertising by Atari. In either event, the game saw approximately 12,000 copies sold in the years of 1987 and 1988, with nothing in the other years of the Atari Corporation era, so it was seemingly a pretty marginal title by that time. Which makes sense, given that the keyboard controllers and its later variants were effectively abandoned by that point – no title released past 1984 would use them.

Still, if you have the keypads, Codebreaker is a worthwhile game to load up. It’s not the most visually interesting game on the platform to come out in 1978, let alone compared to its fellow two initial keyboard releases, but its pair of logic games holds up well. Just don’t feel bad if you want to bring a notepad along to help with your guesses.

Sources:

Software, Practice and Experience Journal, April-June 1971

They Create Worlds Vol. 1, Alex Smith, 2019

Merchandising, May 1978, January 1979

Atari Corp. 2600 Sales figures, 1986-1990

Atari History Timelines, Michael Current

Strategies for Playing MOO, John Francis, 2010

Mastermind at 50, Duncan Fyfe, March 9 2020