I don’t think it’s a secret that baseball, as a sport, doesn’t lend itself well to early video game consoles. One team is always going to have nine players on the field, while the other is dealing with their batter, along with any base runners they might have on the field at the moment. Meanwhile, the consoles in question typically are limited in resolution, controller input options, and memory. But that didn’t stop programmers and developers from trying their best to translate the popular sport to the video game machines of the day, and eventually they succeeded in making some really good renditions of America’s pasttime. Unfortunately, Atari’s Home Run, released by Sears as simply Baseball, is more of an iterative step on that journey rather than one of the benchmarks.

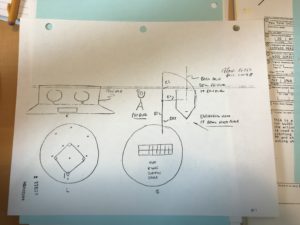

Programmer Bob Whitehead, who wrote Blackjack and Star Ship for the initial VCS lineup, decided to try his hand at tackling baseball next. Whitehead was always a sports fan, but by his own admission he was never very good at playing them himself. But he was one of Atari’s standout early programmers who was getting a handle on the odd capabilities of the VCS, and decided to give it a shot.

He certainly wasn’t the first person to create a baseball video game. In the minicomputer era, a handful of baseball games were written in BASIC, one of which even attempting to recreate the 1967 Major League Baseball World Series. Perhaps more ambitious was Bat Baseball, a visually oriented take on the sport written by T.J. Spence at New York University in 1967 for the CDC 6000 computer. According to court documents held at the Hagley Museum and Library, this program is notable for using a combination of ASCII characters to draw and animate the pitcher and batter: as the pitcher throws the ball, for example, the U that makes up his arms is changed to a J to indicate the throw. The computer keyboard was used to manage pitching and batting. This game was notable enough to be mentioned in court proceedings when Magnavox was fighting for its video game patents in the ensuing decades, but it’s unclear what legacy it contains beyond that.

One of the earliest commercial games came from arcade developer Ramtek. Known simply as Baseball, Ramtek’s game would be licensed out to Seeburg as Deluxe Baseball and Midway under the name Ball Park. While all these played the same, Ramtek’s original TTL-based rendition featured a top-down view of a baseball field within a cabinet designed to make it seem like the monitor was in the middle of a stadium. What’s more, this game likely features some of the earliest animated humans in a video game – the next closest to that claim may be the 1973 computer game Moonlander. Ramtek’s TTL baseball would end up being remade as a microprocessor-based arcade game in 1976 by John Metzler, while Midway development partner Dave Nutting Associates worked on its own remake under the name Tornado Baseball as one of its first microprocessor projects – notably using a mirror to superimpose the action overtop a model of a baseball field. This particular version would eventually be ported to the Bally Professional Arcade game console by the same developers. Midway would follow Tornado Baseball up with near-annual arcade successors, while at Atari, developer Dave Sheppard wrote his own rendition of an arcade baseball game, called Flyball. But while arcade games were usually popular sources of inspiration for Atari’s developers, Whitehead said he hadn’t really seen any of these titles before starting work on what would become Home Run.

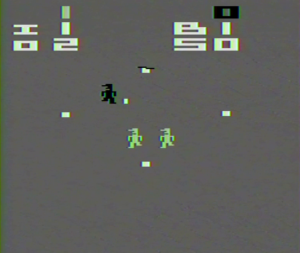

And Home Run is absolutely constrained by the VCS’s limitations. While you do get a rendition of the baseball diamond, depending on the gametype the fielding team only has one, two or three players at a time, multiplexed into a row – like the triple biplanes in Combat. The batting team does show players moving between bases, and even has the characters on base, but you have no option to try and steal a run. On top of that, the game suffers from some serious flickering while runners are on the move; this technique would alternate which sprites would appear on the line each frame, which allows for more sprites than the game could normally show at once, but it was also a trick that Whitehead disliked – a factor in his decision to feature almost no flickering if he could help it in future games.

Since fielding is functionally nonexistent, the gameplay loop is a bit different from the real sport. The pitcher will throw the ball at the batter, where the usual array of fouls, strikes, and balls are pretty well represented. The pitcher can use the controller to shift the ball left and right, and even vary the speed after it’s been thrown. On a hit, the pitcher and any fielders must run to catch the ball; if it’s caught they then have to physically touch the base runners to take them out. There’s no throwing to other bases, there’s no catching a fly ball to get an automatic out, just racing around the field. It actually kind of works; Home Run takes the basic idea of baseball being a duel between the pitcher and the batter and makes that the entire game. The difficulty switches allow for changing the speed of the fielders, which can end up making it trickier to get outs with a single person, but basically balances the game out when you’ve got three – particularly if the gametype has the fielders spread out rather than bunched together. Finally, Whitehead included a surprisingly competent computer opponent in the game just in case the player couldn’t find a human to play against; he said it was tricky to implement a computer opponent in the first set of VCS games, but with improved development tools and more familiarity with the platform – plus having relatively simple games – it was manageable to program out a computer team for Home Run.

Since fielding is functionally nonexistent, the gameplay loop is a bit different from the real sport. The pitcher will throw the ball at the batter, where the usual array of fouls, strikes, and balls are pretty well represented. The pitcher can use the controller to shift the ball left and right, and even vary the speed after it’s been thrown. On a hit, the pitcher and any fielders must run to catch the ball; if it’s caught they then have to physically touch the base runners to take them out. There’s no throwing to other bases, there’s no catching a fly ball to get an automatic out, just racing around the field. It actually kind of works; Home Run takes the basic idea of baseball being a duel between the pitcher and the batter and makes that the entire game. The difficulty switches allow for changing the speed of the fielders, which can end up making it trickier to get outs with a single person, but basically balances the game out when you’ve got three – particularly if the gametype has the fielders spread out rather than bunched together. Finally, Whitehead included a surprisingly competent computer opponent in the game just in case the player couldn’t find a human to play against; he said it was tricky to implement a computer opponent in the first set of VCS games, but with improved development tools and more familiarity with the platform – plus having relatively simple games – it was manageable to program out a computer team for Home Run.

While this all makes Home Run sound like an oddball version of the sport, Whitehead’s solutions weren’t far off of what other home baseball developers came up with to get around the input or memory limitations each competing console has. By virtue of being on the VCS, Home Run did have a comparatively sizable install base to work with… though competing platforms were publishing their own versions before or contemporaneously with Atari’s game. The first off the plate was Andy Modla’s Baseball for the RCA Studio II, coming out in June 1977.

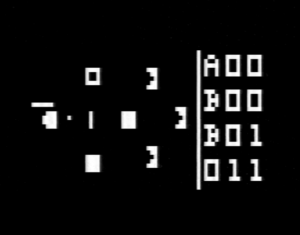

Modla explained that the folks in marketing were insistent that the system should have a baseball game. He didn’t think it would be doable the way he wanted, where you could see the full arc of the field vertically up the screen – the Studio II just doesn’t have that screen resolution. To accommodate this, he flipped the field 90 degrees, and with input from Dick Rainboth in the sales and marketing department, he was able to match the rules to the real game. Modla said it was the best he could do with the system, and while it’s a bit rough, the effort is commendable. The Studio II baseball game has three mitt-shaped fielders the pitching team can control, though they can only move up and down and would only successfully catch a ball if it lands in the appropriate part of the sprite. Whiffing a catch meant the batter get runs onto the bases. On top of that, it lacks any real way to control the pitch other than speed. The batter, meanwhile, has to ensure their swing is timed correctly to catch the ball. While RCA did not appear to track sales of individual cartridges, according to a February 1978 memo baseball was the title written in most often on product registration cards as a cartridge purchased.

Modla explained that the folks in marketing were insistent that the system should have a baseball game. He didn’t think it would be doable the way he wanted, where you could see the full arc of the field vertically up the screen – the Studio II just doesn’t have that screen resolution. To accommodate this, he flipped the field 90 degrees, and with input from Dick Rainboth in the sales and marketing department, he was able to match the rules to the real game. Modla said it was the best he could do with the system, and while it’s a bit rough, the effort is commendable. The Studio II baseball game has three mitt-shaped fielders the pitching team can control, though they can only move up and down and would only successfully catch a ball if it lands in the appropriate part of the sprite. Whiffing a catch meant the batter get runs onto the bases. On top of that, it lacks any real way to control the pitch other than speed. The batter, meanwhile, has to ensure their swing is timed correctly to catch the ball. While RCA did not appear to track sales of individual cartridges, according to a February 1978 memo baseball was the title written in most often on product registration cards as a cartridge purchased.

Meanwhile, the Channel F version, also simply named Baseball, came along a couple months later in September. Written by Don Ruffcorn – who would later go on to write a couple VCS games for Telesys – this rendition does have human players at the bases and across the field, but still only allows direct control over the outfielders. Similar to the VCS game, it features pretty robust control over the pitching speed and direction, even after throwing the ball. You can even bean the batter and give them a run if you’re not careful, though the graphics don’t portray the bases or the baseline. On the whole it is fairly comparable to the Studio II game that came out a few months prior, if more visually interesting. Fairchild’s game was considered by Xenia Gazette writer Dick Cowan to be one of the best games on the platform, though in a December 1978 column he describes Home Run as being substantially better, thanks to the ability to handicap teams, play the computer, and to make double and triple plays if you’re quick enough.

Meanwhile, the Channel F version, also simply named Baseball, came along a couple months later in September. Written by Don Ruffcorn – who would later go on to write a couple VCS games for Telesys – this rendition does have human players at the bases and across the field, but still only allows direct control over the outfielders. Similar to the VCS game, it features pretty robust control over the pitching speed and direction, even after throwing the ball. You can even bean the batter and give them a run if you’re not careful, though the graphics don’t portray the bases or the baseline. On the whole it is fairly comparable to the Studio II game that came out a few months prior, if more visually interesting. Fairchild’s game was considered by Xenia Gazette writer Dick Cowan to be one of the best games on the platform, though in a December 1978 column he describes Home Run as being substantially better, thanks to the ability to handicap teams, play the computer, and to make double and triple plays if you’re quick enough.

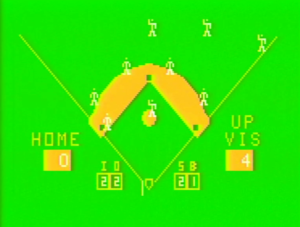

1978 brought along with it a new line of consoles, each featuring their own halting advancements to baseball video games with gameplay improvements that put them a step up from Home Run. Bally’s Professional Arcade console was arguably the most powerful machine on the market at the time, and its port of Midway’s Tornado Baseball game is a standout in speed and presentation, even if it plays pretty similarly to Fairchild’s Channel F rendition. While players are still limited to essentially just controller the outfield, we now have a full baseball field drawn on the screen, with clear cut boxes for the score, the number of balls, strikes and outs, and the inning. The Bally’s sound capabilities are also on display here, with Tornado Baseball featuring a cheering crowd with a succesful bat. As an aside, Tornado Baseball was included on a cart with Bally’s various Pong clone games because of Magnavox’s patents – this way the company only had one release featuring all the potentially problematic games.

game is a standout in speed and presentation, even if it plays pretty similarly to Fairchild’s Channel F rendition. While players are still limited to essentially just controller the outfield, we now have a full baseball field drawn on the screen, with clear cut boxes for the score, the number of balls, strikes and outs, and the inning. The Bally’s sound capabilities are also on display here, with Tornado Baseball featuring a cheering crowd with a succesful bat. As an aside, Tornado Baseball was included on a cart with Bally’s various Pong clone games because of Magnavox’s patents – this way the company only had one release featuring all the potentially problematic games.

Magnavox’s Odyssey2 baseball game, released in September alongside the console, allows for the ball to even just land on the field, requiring fielders to pick it up and throw it to the basemen. While visually less interesting than the Bally release, the game uses the Odyssey2’s built in humanoid sprite to full effect to produce a flicker-free game of ball.

Finally, landing somewhere between the Odyssey2 and Bally Arcade renditions is the APF MP1000 baseball game, aptly named Baseball. Debuting in the fall alongside that system, it features some of the same bells and whistles as the Bally and Channel F versions, but includes a computer opponent – the only one of these games besides Home Run to do so. This, alongside the colorful and well-defined visuals, make it one of the better renditions on the market – even if the MP1000 was scarcely a blip in the console space.

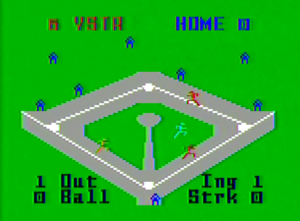

But truly the gold standard for this first wave of home console baseball games was reached with Mattel’s 1980 Major League Baseball, published on the Intellivision console during the system’s test market phase early in the year. MLB doesn’t feature a computer opponent, but thanks to the keypad and the 16-directional disc on the Intellivision controllers, it allowed for a more realistic take on the sport, one where all the players on the field can be useful and controlled by the player. Batters can swing for the fences or even just opt to bunt, adding new strategy to  video baseball games. The difference between Mattel’s game and what had come before was so stark that Mattel made direct comparisons to Home Run a part of their fall advertising campaign, openly taking on the market leader Atari at a time when that was a highly unusual tactic. This proved to be utterly successful – while Mattel’s early marketing efforts built around the ill-fated keyboard component garnered little response, this comparison to Atari and focus on the games led the company to sell out of its entire stock of 175,000 Intellivisions by the end of the year, with Major League Baseball itself selling 132,200 copies according to an internal company memo – more than any game but the pack-in Las Vegas Poker & Blackjack. This said, Mattel recognized the massive sales gap between the Intellivision and the Atari VCS, and would eventually port this game to the VCS in 1982 as Super Challenge Baseball – a remarkably faithful adaptation of the original within the VCS’s constraints. While Major League Baseball is not the arcade-style take on the sport that its competitors had gone with, this didn’t seem to bother the contemporary press, retailers or consumers.

video baseball games. The difference between Mattel’s game and what had come before was so stark that Mattel made direct comparisons to Home Run a part of their fall advertising campaign, openly taking on the market leader Atari at a time when that was a highly unusual tactic. This proved to be utterly successful – while Mattel’s early marketing efforts built around the ill-fated keyboard component garnered little response, this comparison to Atari and focus on the games led the company to sell out of its entire stock of 175,000 Intellivisions by the end of the year, with Major League Baseball itself selling 132,200 copies according to an internal company memo – more than any game but the pack-in Las Vegas Poker & Blackjack. This said, Mattel recognized the massive sales gap between the Intellivision and the Atari VCS, and would eventually port this game to the VCS in 1982 as Super Challenge Baseball – a remarkably faithful adaptation of the original within the VCS’s constraints. While Major League Baseball is not the arcade-style take on the sport that its competitors had gone with, this didn’t seem to bother the contemporary press, retailers or consumers.

Home Run itself was a centerpiece of Atari’s own late 1978 advertising campaign, but Major League Baseball’s release meant that the game was generally side-eyed in the game press from 1980 on. For example, the game had a fairly positive writeup in Video Magazine’s summer 1979 Arcade Alley column, which provided some advice on how to play well and beat the computer. Come the June 1982 Electronic Games article about baseball video games, however – written by some of the same people – the writers note that it doesn’t really give the feeling of real sports action, relegating it to the role of “benchwarmer” among the baseball genre.

Around June 1981, Atari started trying to move copies of Home Run as free games to anyone who purchased two other sports titles on the VCS, Golf and Basketball. The company ultimately seemed to have largely phased out Home Run in its advertising sometime in 1982 in favor of their new, more realistic game Realsports Baseball, which launched that October. Despite that frankly superior version of baseball being on the market, Home Run seemed to stick around in some capacity, as Atari continued selling tens of thousands of copies of the game through 1989.

Around June 1981, Atari started trying to move copies of Home Run as free games to anyone who purchased two other sports titles on the VCS, Golf and Basketball. The company ultimately seemed to have largely phased out Home Run in its advertising sometime in 1982 in favor of their new, more realistic game Realsports Baseball, which launched that October. Despite that frankly superior version of baseball being on the market, Home Run seemed to stick around in some capacity, as Atari continued selling tens of thousands of copies of the game through 1989.

Despite Whitehead’s first foray into sports games on the VCS being one that he looks back on as being clunky, it can make for a pretty quick and entertaining take on the sport with a second player, albeit one that is not terribly baseball-like. Whitehead would go on to develop a few more VCS sports games before moving over to the Commodore 64 computer and designing the seminal baseball game Hardball, proving that you just might need to take another swing to land that home run.

Sources:

Author interview with Bob Whitehead, September 4 2018

Author interview with Andy Modla, June 18 2021

Author interview with Rich Olney, February-July 2020

All in Color for a Quarter, Keith Smith, 2016, unpublished manuscript

Moonlander: One Giant Leap for Game Design, Kate Willaert, 2021

Internal RCA Memo, February 1978, Hagley Museum & Library, Joe Weisbecker Papers, M&A 875

Magnavox v. Sega court documents, Hagley Museum & Library, Bernard Lechner Papers, M&A 1191

Mattel Electronics Intellivision internal sales memo, June 1983, courtesy the Blue Sky Rangers

They Create Worlds, Alex Smith, 2019, 418

Atari Corp. 2600 Sales figures, 1986-1990

Atari History Timelines, Michael Current

Xenia Gazette, December 1 1978

Video Magazine, Summer 1979

Electronic Games, June 1982