If you’re going to sell a specialized controller, it’s important to ensure you have games that are going to make good use of it. It’s unlikely that Breakout would have worked particularly well if it didn’t have the paddle controller, and Brain Games makes excellent use of the keyboard controller to allow the player to tap a specific key to do exactly what they want. Which brings us to today’s game, Alan Miller’s Hunt and Score: the game uses the keyboard controllers pretty well, but it probably could have worked just fine without them.

Hunt and Score is the VCS take on a memory match game, which is not coincidentally the title Sears sold it under. You’ve got an array of squares, each with some kind of object underneath. The player’s goal is to match two identical objects in a turn. This incredibly simple concept has likely existed for at least as long as playing cards and their equivalents have, with the card game known under the title Concentration. And here, Miller brings that card game to the home console, without any need to shuffle a deck or clean up afterwards.

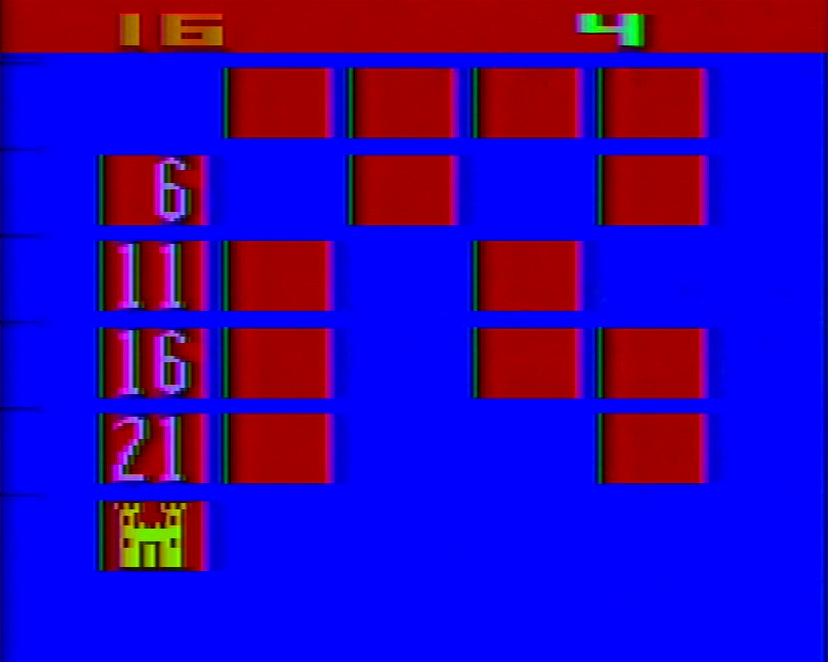

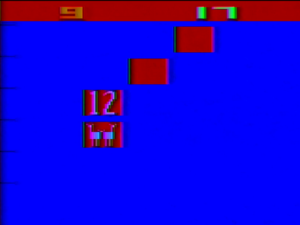

And you know, it’s fine. The game has options for one or two player games with grids of either 16 or 30 squares, with an additional option to include “wild cards” that can be matched with any other object. The difficulty switches adjust whether or not the player in question will get one point or two points per correct match. With a successful match, the player scores points and gets to try again. With a wrong match, the turn shifts over to the other person in a two-player game; otherwise the computer scores a point and the player gets to try again. Every square has numbers on them; you simply type in the number of the square you want to flip on the keypad and then push the number sign key to enter in your pick, or push the asterisk to erase it.

At the same time, Flag Capture showed us that this sort of grid display could have been done with a joystick and work pretty well. There’s nothing wrong with the keyboard controls for this game, but it doesn’t really take the best advantage of them. There’s also not much to it other than a bit of luck and having a good memory; it’s a good game for children and those who want to work out their short term memory skills, but it’s certainly one of the least exciting games in the VCS’s 400+ cartridge library.

In 1980, the game’s title would be changed to A Game of Concentration to match the name of the card game – probably a good choice, as Hunt and Score doesn’t really describe what’s happening in the game particularly well. It would continue to be sold under this title through the Warner-Atari years, and a further 13,000 copies would be sold during the Atari Corporation years in the late 1980s, ending with a whopping 70 Concentration carts being sold in 1988.

This is also the final first-party VCS game we’ll be looking at from Alan Miller. Upon finishing his 1978 games Hangman, Basketball and Hunt and Score, Miller was shifted over to work on the Atari 8-bit computer line’s operating system. His final game for the company would be a conversion of Basketball to the Atari computer before he left alongside a group of other programmers to found Activision, the first third-party video game company.

Because it requires a certain degree of graphical ability and is primarily geared towards younger players, these Match games don’t seem to be prevalent on early computer systems – the earliest example I’ve found is Match on RCA’s FRED prototype computer, which sees two players alternating turns to match numbers, letters, and symbols using the machine’s hex keypad. A 1 or a 2 appearing on the board after a match indicates which player gets credit for it. This reasonably playable take on the game presaged memory match games appearing on home consoles a few years later, such as the VCS and its competitors.

The Fairchild Channel F’s version, aptly titled Memory Match, has one or two players flipping tiles to match either symbols or numbers. The game allows for either 24 or 40 tiles and either regular or “super” modes; the only difference is that the super modes may include multiple pairs of some numbers or symbols. In the number games, the digit that is paired will earn the player that same number of points; matching a six will give them six points, for example. The symbols are all worth one point. This makes the number games somewhat more interesting, as it can leave players either targeting the high value numbers or trying to sweep up the lower values – though in either event, you have to remember where everything is pretty quickly. Since the channel F controllers use knobs, not keypads, this plays a little more like Flag Capture, and doesn’t really detract from the game.

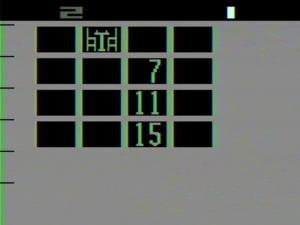

RCA had a memory match game, dubbed Concentration Match, completed and ready to go for its Studio III console when it was shelved and canceled. The game was ultimately released by Conic after the Hong Kong-based company licensed the Studio III technology and game library and sold it in Europe and Asia. The game runs fine on North American Studio II consoles, though, and uses the system’s keypads to great effect. This version uses both the buttons on both keypads to each represent one of 18 tiles on the screen. The letters A and B on screen indicate which player is up at the machine, and they also have the option of seeing what all the symbols are at the start of the game, depending on what button is pressed to begin. The button-per-tile setup is incredibly intuitive, and while the game itself may not be that exciting, this is probably the most elegant control solution from that time.

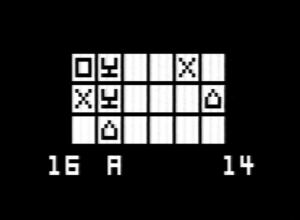

The Odyssey2 Matchmaker Logix Buzzword cart also includes its own take under the titular Matchmaker name. In this version, a matrix of 20 letters – A through T – appear on screen, each with a symbol underneath. Using the keyboard, either one or two players try to match these symbols accordingly. The single player variants are all based on the time it takes to finish the board, while the two-player modes determine the winner based on who makes the most matches, as usual. The use of the keyboard is pretty effective, and less awkward than the VCS’s method of requiring multiple button presses to make a guess.

I will make special note of what APF tried to do in their version of the game, appearing on the cart Bowling/Micro Match. The match game here allows for several different hidden objects, from words to symbols to color patterns, using the keypad on the controllers to input numbers ala the VCS controllers. It also allows for up to four players, and can even require them to match 3 objects in a turn. Whether or not this is a great take on the game is up for debate, but it’s an interesting one, and a few of the options are unique.

Bally also offered up four player action in its Letter Match cartridge for the Professional Arcade. As the name implies, this version opts for letters instead of symbols under the tiles; the higher the difficulty, the more tiles there are to flip. Some tiles are worth extra points if you can match them, and the game will alert you when you turn over one of those. Like the Channel F, you use the control knob to move around and the button to make your pick. There isn’t much else to say about this one, though, other than the audio is surprisingly grating for a Bally release.

Ultimately, all of these games play pretty much the same; there are only so many ways one can dress up Concentration. If you’ve got a VCS, you’re not really missing out on what the other consoles are doing, and vice versa. I wish I could say we’re ending 1978 on a higher note, but I’ll give it this: Hunt and Score is a decent take on a video game genre whose time has long passed.

1978 was a rough year for Atari and the TV game industry as a whole. With the arrival of programmable consoles, the older dedicated machines rapidly fell off the retail market, and retailers remained wary of video games turning into another fad, much as other electronics like CB radios, calculators and digital watches had not long before. While retailers struggled to sell any remaining game systems themselves outside of the holiday season that year, programmable cartridges provided a way for them to make some money year-round, if they were willing to deal with manufacturing delays, and lengthy demonstrations in store. Fairchild continued shipping new games throughout 1978 as a way to break the seasonal cycle for home electronics and try to make some extra money to offset their hardware manufacturing costs, but Atari continued to focus on the traditional holiday-centric marketing cycle. Thanks to research into old newspapers and periodicals, it’s safe to say Atari’s 1978 lineup of games all came out at the same time around October.

Video games also faced pressure from a few other sources: first, retailers wanted to avoid the potential fad nature of TV games by turning to other kinds of electronic games, notably dedicated handhelds – these proved to be hot sellers. The trinity of personal computers – the Commodore PET, the TRS-80, and the Apple II – also became available, and while they were much more expensive than a video game console, they were also decidedly more capable, and the stores willing to stock and sell those and other personal computers found that they were getting solid sales among those people willing to shell out for them. Nevertheless the computer market would remain a tiny niche outside of the business world until more affordable options became available in the early 1980s.

In the end, Atari produced 800,000 VCS units for the Christmas season in 1978, but retailers only ordered about 550,000 of them. Selling out was preferable to having to deal with the leftover machines in the new year, and making too many units was a major factor in Atari’s profit margins dropping from 40 million in 1977 to 2.7 million dollars for 1978. Between all the companies producing programmable and dedicated video games, roughly 2.5 million hardware units would reportedly be shipped to retail that year – fewer than the previous year, as the dedicated market shrunk, but this just provides another glimpse into how small the retail market was in the US for video games.

Following the relatively poor holiday sales, Atari’s founder, Nolan Bushnell, would be pushed out from his company president position on December 28th, with Ray Kassar taking over the job. Kassar decided that Atari would follow in Fairchild’s footsteps and start having new games stocked throughout the year in 1979, with more moderate hardware production plans. While 1979 would remain a year where the VCS swam in a relatively small commercial pond, the lineup would improve upon 1978’s in complexity and in quality. By the end of the year, the stage will be set for the VCS market to explode mere months into 1980. But for now, we bid goodbye to the sophomore year of the VCS. Breakout, Basketball, and Outlaw in particular would continue to sell well throughout the console’s lifespan, and several of these games represented the first attempts from some truly great developers who would go on to define the platform.

Sources:

Atari: Business is Fun, Marty Goldberg and Curt Vendel, 2012

They Create Worlds Vol. 1, Alex Smith, 2019

Merchandising, February 1978, June 1978, July 1978, August 1978, January 1979

Electronic Games, July 1982

Alan Miller, interview with Al Backiel, Digital Press, Sept/Oct. 2002

decle says:

Apologies for vandalising this page, but I can’t leave comments on the Intellivision release date list. Firstly, kudos for all the work you’re doing. It’s excellent. I managed to accidentally repeat much of your analysis of Inty release dates from VGU before discovering your page. In doing so, I think I’ve noticed a couple of discrepancies, for example I think you missed the release of Super Cobra in October 83. Feel free to PM me at decle on Atari Age if you’d like to discuss it further. Cheers.