Coming as it did at the tail end of westerns’ day in the sun, the old American west might not be the most popular setting in video games, but it has popped up a few times over the years, from Wild Gunman to Sunset Riders up to the recent Red Dead Redemption games. But if you want to see an early example of a video game western, then Outlaw has you covered.

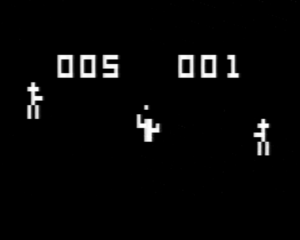

Outlaw was developer David Crane’s first game on the VCS, where he would go on to become one of the most prolific gamemakers on the platform. We’re years away from his seminal works like Pitfall, but even this first outing is a solidly replayable two-player game, where two cowboys shoot bullets at each other, competing to see who can hit the other 10 times. The premise isn’t original to Crane, however – he was interested in writing a home conversion of Midway’s 1975 arcade game Gun Fight.

Gun Fight itself is noteworthy for being the first twin-stick game – as each player has a stick for moving and another for aiming and firing their gun – and for among the very first microprocessor-based video game released, using an Intel 8080. While RCA had developed a microprocessor-based arcade platform based on their 1801 microprocessor design and even location-tested it in 1975, this never made it to full production. Another company, Mirco, also had a microprocessor based game out at the same time as Gun Fight called PT 109, but it was a major flop.

And in fact, Gun Fight didn’t start out with a microprocessor; the game is something of an officially licensed conversion of Taito’s Japanese arcade game Western Gun, first tested in September 1975. Western Gun doesn’t use a

microprocessor at all, and was built using the same transistor-transistor logic (or TTL) circuit design every other arcade game before it relied on; there’s no programming involved at all. Tomohiro Nishikado, who would go on to famously develop Taito’s Space Invaders arcade game, started work on Western Gun after deciding there were practically no “gun games” in arcades, recalling that Sega’s own electromechanical Gun Fight machine was rather successful. According to a 2017 biography of Nishikado by Florent Gorges, he first created two squat, cartoonish cowboys and designed circuitry to allow them to move freely around the field, with a three-step level adjusting their aim. Nishikado then added the rocks and cacti to the playfield to create obstacles players could hide behind, introducing with it the strategy and fun the game was lacking earlier in development. Nishikado would end up being in charge of all the marketing art, and the stylized, almost “super deformed” style he chose for Western Gun was reportedly well received. Taito ended up licensing their game to Midway for a US release, but the basic concept of two cowboys shooting at each other is functionally the only thing that the two versions have in common.

Midway’s executives felt that the cutesy graphics of Western Gun wouldn’t be appealing to American audiences, and passed along development of a US version of Western Gun to development studio Dave Nutting Associates. Fortuitously, this was where engineer Jeff Fredriksen was exploring how microprocessors could be used in arcade games. Fredriksen had worked an Intel 4004 into a pinball machine called Flicker, though Bally (the parent company of Midway) opted against producing it. Instead his pinball system would be used for The Spirit of 76, published by Mirco Games with a Motorola microprocessor instead. Fredriksen found the 4004 wasn’t powerful enough to drive a display, choosing instead its big brother the Intel 8080. His system would allow bitmap displays to be drawn on the screen, with the microprocessor instructing how and which ones would be active in each frame. The end result was a system that could produce more elaborate graphics and animation than TTL games had up to that point. Their test program was what would become The Amazing Maze, but Gun Fight would soon be their first commercial product.

In contemporary interviews and the Gun Fight service manual, Midway staff argued that microprocessor-based games would be easier to service since they had fewer parts to deal with, were quicker to develop, easier to swap out for other games, and overall were better investments than their logic-based counterparts. Tom McHugh, one of the people who programmed the American version of the game at developer Dave Nutting Associates, has said he didn’t even see Western Gun in action before being given the assignment; McHugh’s boss Dave Nutting had simply told him that they were doing the game with a microprocessor and handed him the design he’d come up with to implement. The cowboys were redesigned to have more realistic proportions, and the fixed playfield of Western Gun was dropped in favor of a dynamic one that changes after each round, with obstacles such as cacti, trees, and moving stagecoaches appearing. The pacing of the game was different – which Nishikado wasn’t a fan of – but Gun Fight proved to be a big success with 8600 units sold.

Interestingly, DNA’s choice to develop Gun Fight as a microprocessor game would inspire Nishikado to put together his own microprocessor game development system that he would use to create Space Invaders in 1978. Without Western Gun – which begat Gun Fight, which in turn begat Outlaw – we wouldn’t have Space Invaders, and without the Atari VCS conversion of Space Invaders, the VCS would likely never have become a juggernaut. Weird bit of poetic symmetry there.

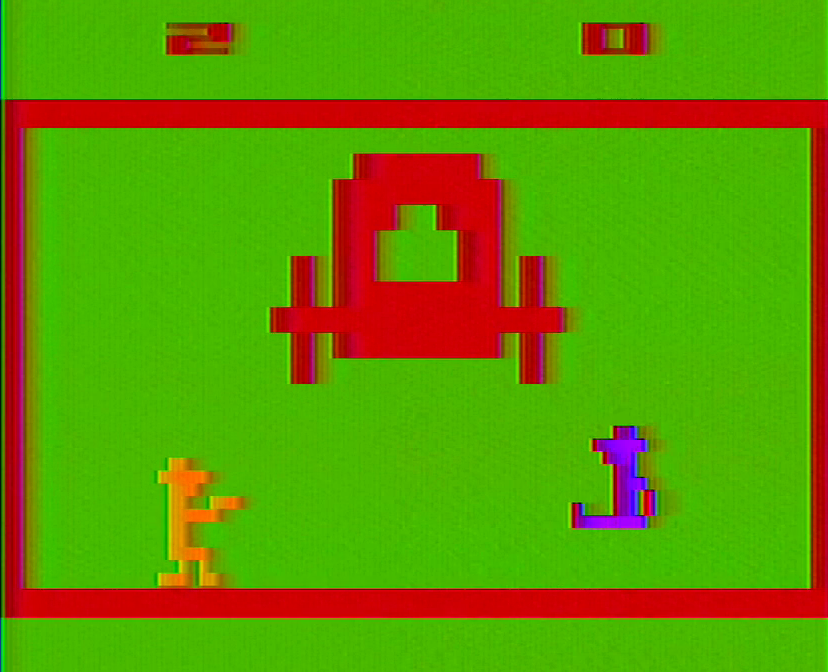

Which brings us back to Outlaw, also released by Sears under the name Gunslinger. Crane reduced the controls down to one stick and button, and it works reasonably well. The stick controls your movement; to aim and fire, the player presses and holds the button to stop and get into a firing position, aims using the stick, and then lets go of the button to fire their bullet. Bullets can ricochet around the screen, allowing for more firing angles to hit your target.

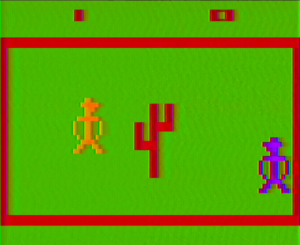

Crane used a few interesting, albeit not earth-shattering, tricks to make the game work on the VCS. The cowboys and their bullets use the system’s allotted two sprites and missiles, while the obstacles in the middle are done entirely using lower-resolution background graphics. These background obstacles are written into the VCS’s RAM, which allows them to be manipulated – in some gametypes, you can shoot bits of them off to allow yourself more firing angles. It’s even possible to shoot yourself a big enough opening to walk through to the other side, though since your cowboy doesn’t turn around this can quickly become a terrible risk for no reward.

Crane used a few interesting, albeit not earth-shattering, tricks to make the game work on the VCS. The cowboys and their bullets use the system’s allotted two sprites and missiles, while the obstacles in the middle are done entirely using lower-resolution background graphics. These background obstacles are written into the VCS’s RAM, which allows them to be manipulated – in some gametypes, you can shoot bits of them off to allow yourself more firing angles. It’s even possible to shoot yourself a big enough opening to walk through to the other side, though since your cowboy doesn’t turn around this can quickly become a terrible risk for no reward.

Outlaw’s variants are all what you’d expect. There are options for different obstacles in the center of the screen, including a cactus, a moving stagecoach, or a literal wall. Some options limit each player to six bullets to hit their

opponent, requiring both players to run out before getting a restock. The Blowaway gametypes allow for the aforementioned object-clearing bullets – in other games, they simply stop if they hit something with no consequence. Finally, there are Getaway gametypes that allow players to move immediately after firing rather than waiting for their bullet to disappear. While the gametypes with all of the limited ammunition,getaway and moving obstacle options are more interesting to play, they are on the whole unremarkable for a game about two people shooting at each other. In case a second player was unavailable, the game includes a single player shooting gallery variant with a bouncing target the player must try and shoot 10 times within 99 seconds. Finally, the difficulty switches change whether or not a bullet in flight will disappear if the cowboy who fired it is hit. Crane said that over his career he found himself uninterested in adding an array of gametypes to his titles, as was Atari’s house style at the time; he said he felt this was leaving too much up to players. Rather, he found himself preferring to make one set of interesting features and leaving it at that.

Fortunately, the underlying game to Outlaw is solid. It all comes down to timing and being willing to take measured risks to get your shots in and then move back to safety. The large character sprites and relatively slow walking speeds limit how well you can effectively dodge, but this just means games don’t tend to last very long. Reading between the  lines of the game’s review in the July/August 1978 edition of Creative Computing, they also seemed to approve of it. David Ahl indicated that he and fellow reviewer Chris Cerf found the game hilarious to play (and difficult to fire straight) after a couple glasses of wine. The sprites may be chunky, but there is a surprising amount of comedic personality that comes through when one cowboy is shot and just plops down on the ground. Space Gamer reviewed the title in its December 1980 issue, where Eric Thompson wrote that he had few complaints with the game (mostly relegated to the gun being hard to see and the learning curve for new players) and ultimately recommended it. Dick Cowan reviewed Outlaw in the pages of the Xenia Gazette newspaper under its Sears title Gunslinger, calling it one of the better Atari cartridges and writing that “it has so many different variations that it’s bound to sustain interest for extended periods of time.”

lines of the game’s review in the July/August 1978 edition of Creative Computing, they also seemed to approve of it. David Ahl indicated that he and fellow reviewer Chris Cerf found the game hilarious to play (and difficult to fire straight) after a couple glasses of wine. The sprites may be chunky, but there is a surprising amount of comedic personality that comes through when one cowboy is shot and just plops down on the ground. Space Gamer reviewed the title in its December 1980 issue, where Eric Thompson wrote that he had few complaints with the game (mostly relegated to the gun being hard to see and the learning curve for new players) and ultimately recommended it. Dick Cowan reviewed Outlaw in the pages of the Xenia Gazette newspaper under its Sears title Gunslinger, calling it one of the better Atari cartridges and writing that “it has so many different variations that it’s bound to sustain interest for extended periods of time.”

Midway’s Gun Fight arcade game was enough of a success that Atari was not the only company looking to bank on it with home versions. RCA’s own 1977 release Gunfighter is among the very first games written by their programmer Andy Modla for the Studio II, and apes the basic concept pretty well. Modla said he had seen the game at an arcade

around the fall of 1976 and thought it would be cool to try and create a version of that himself. had written it as an exercise to see what the hardware was capable of and its limits. What he found over the course of the roughly 6-8 weeks it took to write Gunfighter (and its companion game on the cartridge, Moonship Battle) was the system was not well-suited to fast paced action games. Players are limited to only moving up and down and there’s not much in way of options, but the game plays reasonably well and includes a computer opponent, something Modla remarked that he added because he liked having a little something extra in all his games to set them apart. Dick Rainboth from the marketing side of the Studio II project rewrote Modla’s basic instructions into the manual and cartridge directions text, and brought in an artist – unknown today – to create the box art. Despite being one of Modla’s first creations, this would be one of the later releases for the Studio II, with the earliest reports of its availability coming up in September 1977.

More involved are the other two home versions that came along after RCA’s game system was dropped. The first is an official home version of Gun Fight found on the Bally Professional Arcade as a built-in game. Written by Alan McNeil, this version is unique in that you can use the spinner on the Bally controller to fine tune your firing angle instead of just pushing up or down to slightly angle your shots like on the Atari version. According to Jamie Fenton, who led the software end of the Professional Arcade’s development at Dave Nutting Associates, they were able to pull from the logic used in the arcade original to ensure it played very close to its big brother. As a result, this could readily be considered the best Gun Fight home version of its time.

Magnavox had its own version with August 1979’s Showdown in 2100 AD for the Odyssey2 – known simply as Gunfighter in Europe – where players are ostensibly controlling cowboy robots in a shootout. Despite the odd premise, the game is well animated, though the animation also ends up giving it a more deliberate pace than its competitors. Bullets can bounce off of trees and other obstacles, though you are limited to firing in a horizontal line. If you run out of bullets, touching the rock that matches your player color will reload your gun; the game even features a computer opponent too if no one touches the second controller. This was one of many games produced by Ed Averett as a contractor for Magnavox, and while it may not be his finest work on the platform, it is a solid game.

The VCS itself played host to a fast-paced homebrew rendition of the arcade game called Gunfight in 2001. This version of the Gun Fight even has a rendition of Johnny Cash’s “Ring of Fire” song for its opening tune, and a computer opponent. It’s hard to go back to Outlaw after giving Gunfight a whirl, but the latter benefits from decades of programming expertise being developed for the VCS so it’s not entirely a fair comparison.

Atari debuted Outlaw during a press conference written up in the May 1978 edition of Merchandising, and it appears to have shipped out with the rest of 1978’s games around October of that year. Unfortunately, we don’t have much information on how Outlaw sold over the following years. Atari Corp’s internal sales figures indicate they had sold roughly 7,500 copies of the game between 1986 and 1988, the last year it appears in their data; not among the most impressive sales figures they had for older titles, but a respectable number. It does also appear in practically all of Atari Inc.’s catalogs through 1983, which does suggest it had strong enough legs to keep it on the market through the VCS’s heyday. And anecdotally, it is a fairly common game to find even now, which does indicate if nothing else Atari made a whole lot of copies over the years.

Atari debuted Outlaw during a press conference written up in the May 1978 edition of Merchandising, and it appears to have shipped out with the rest of 1978’s games around October of that year. Unfortunately, we don’t have much information on how Outlaw sold over the following years. Atari Corp’s internal sales figures indicate they had sold roughly 7,500 copies of the game between 1986 and 1988, the last year it appears in their data; not among the most impressive sales figures they had for older titles, but a respectable number. It does also appear in practically all of Atari Inc.’s catalogs through 1983, which does suggest it had strong enough legs to keep it on the market through the VCS’s heyday. And anecdotally, it is a fairly common game to find even now, which does indicate if nothing else Atari made a whole lot of copies over the years.

And it really isn’t hard to see why. Outlaw does a good job in capturing the appeal of early head-to-head VCS games. It’s intuitive to learn and play, matches are over fairly quickly, and once you settle onto the variations that work for you, it remains one of the more entertaining titles from the console’s first few years. And as for David Crane, we’ll be seeing a lot more of his work in the future as he becomes one of the most prolific, inventive and successful developers in the platform’s history.

Sources:

The Man Who Created Space Invaders, Florent Gorges, 2018

They Create Worlds, Vol. 1, Alex Smith, 2019, 274-275

David Crane, correspondence with the author, August 17 2017

Andy Modla, interview with the author, June 18 2021

Jamie Fenton, interview with the author, December 2 2020

Tom McHugh, interview with Ethan Johnson, April 15 2017

Creative Computing, July/August 1978

Xenia Gazette, February 24 1979

Merchandising, May 1978

Atari History Timelines, Michael Current

Exploring the First Microprocessor Video Games, Ethan Johnson, September 11 2018

All in Color for a Quarter, Keith Smith, unpublished manuscript, 2016