The Atari VCS was supported commercially on the market for a mind-boggling 14 years, starting in 1977 and ending its run in 1991. There are a handful of incredibly notable moments in time during the system’s life on the market, and March 1980 might be the most important one for the console’s fortunes – and for those of the home video game industry in North America. It was that month that one of the biggest VCS games ever published, Space Invaders started hitting store shelves, a cartridge that can be directly credited with making the VCS the runaway hit and social icon for the era that it became. Simply put: without Space Invaders, the VCS probably would have never survived another 11 years, let alone to have the kind of afterlife it’s seen since then.

Space Invaders didn’t become a massive success on the VCS in a vacuum, however. To talk about how huge the game became, you first have to consider the source.The VCS cartridge is a home conversion of Taito’s incredibly successful and iconic 1978 Space Invaders arcade game. This was the creation of Tomohiro Nishikado, a game designer who had previously worked on a handful of electro-mechanical and transistor-transistor logic (TTL) video games, such as Sky Fighter, Soccer and Speed Race. Despite his comfort level with this older technology, Nishikado said he recognized that microprocessor-based games were necessary following the release of Midway’s Gun Fight in 1975. This was a licensed rendition of Taito’s TTL-based Western Gun, which Nishikado had also designed, redeveloped effectively from the ground-up by Tom McHugh and the titular Dave Nutting of Dave Nutting Associates. Other than the premise of cowboys shooting at each other across the screen, the two games played and looked quite differently, and while Nishikado was dissatisfied with the changes made for Gun Fight, he couldn’t argue that the microprocessor allowed for more complexity than he could realistically get out of transistor logic.

Since this would be the first such game developed in Japan, Nishikado had to figure out a way to build his own development environment. Given the costs of importing an entire development system, Nishikado instead ordered LSI computer chips, soldered them onto a board, and programmed to them directly using assembly language and a physical chart with the necessary hexadecimal conversions. Taito brought in schematics and actual boards for both Gun Fight and another Midway game using a microprocessor, Sea Wolf, for Nishikado to analyze as part of his work. For the game itself, Nishikado was further inspired by Atari’s Breakout, which was a huge hit in Japan and one that made him recognize that you could be incredibly successful with a more esoteric game premise than what he’d done previously. The vertical orientation of the game stuck, but the ball and paddle were replaced with a gun firing at moving targets instead of a wall. Most importantly for the future success of his game, Nishikado expanded upon Breakout’s wave format. When you clear the wall out in Breakout, a second wall appears and the player begins anew; once that’s been cleared the game is over. Nishikado thought it was important to expand on this round progression for his game so that players would be fighting to see who could clear the most waves in an endless series. This sits in contrast to how most arcade games in Japan (and even globally) were set up, where players competed for a high score within a set amount of time or missed shots.

The now-iconic aliens took some time before being introduced into his project. Nishikado said that since players shooting at basic targets was boring, he needed actual enemies that could fight back – something that was incredibly rare for a video game at the time. He initially wanted tanks but felt that they only look cool facing forward, and for a game where the enemies are moving horizontally, it wouldn’t work. His second idea, airplanes, wouldn’t work due to the jerky sprite animation that he was limited to due to the technology available; a similar issue sunk the idea of using ships. Soldiers worked within the limitations, but shooting at people was frowned upon by Taito’s president Michael Kogan, likely due to his experiences surviving the Russian Revolution (his family fled Ukraine for Manchuria in the 1920s), World War II (which he partially spent living in Tokyo) and the Chinese Civil War (having lived in Shanghai between 1944 and 1950); as such one of Nishikado’s direct superiors told him he could not use human troops. The controversy around violence in Exidy’s Death Race in the U.S. could have also been a factor, given that Taito did eventually publish infantry-oriented games such as Front Line. In any event, Nishikado found his solution when by happenstance he came across advertisements for Star Wars during the lead up to its summer 1978 Japanese release, which made him realize that he could use aliens: they wouldn’t look weird moving horizontally or descending down the screen, and people wouldn’t be squeamish about shooting at them. HG Wells’ novel The War of the Worlds and its subsequent 1953 movie led to the marine animal-styled aliens themselves, as that was a popular depiction of aliens at the time. The aliens would be stylized takes on crabs, octopuses, and squids.

The aliens’ increasing speed was simply a limitation of the microprocessor keeping track of so many objects at once – as aliens are destroyed, the processor could move the remaining ones faster. This was part of Nishikado’s game design from the beginning, and it meant he could let the hardware limitations do his work for him instead of actively coding in the speed changes. And with few other options for increasing the difficulty as each wave begins, Nishikado had the idea of simply starting the aliens lower to the screen, giving players less time to react to enemy shots and clear out the armada. He also added a UFO that would fly by periodically. At first blush, the point value for this “mystery ship” seems completely random, but Nishikado said he didn’t have the memory to do such a thing and simply based it on the number of shots that had been fired. Destructible barriers were added to block shots from both the aliens and the player to add some additional strategy and defensive options. For the soundscape, Nishikado worked with Michiyuki Kamei, a recent university graduate. The two were inspired by the music of the movie Jaws to produce the now-iconic four-note thumping bassline that plays every time the invaders move. As the aliens speed up, so too do the notes – producing an effective way to build tension as the game goes on.

According to Nishikado, the game’s original title was Space Monster in homage to a then-popular song by Pink Lady titled Monster, though the actual timing of this doesn’t quite pan out as that single didn’t release until around the same time as the game itself. Regardless of its origins, the name was then changed to Space Invader at the request of Taito management due to Taito already having produced an older arcade game by the Space Monster moniker; pluralizing the latter word to Invaders was a request for international sales and required some programming adjustments, but Nishikado managed to cram in the title change. In all the game took around 10 months to finish, with six of that simply setting up the development equipment needed to actually begin programming. Nishikado said Taito staff members would regularly sneak off to play his game, though others complained they couldn’t reach an end-stage. Game center operators complained about the difficulty during initial showcases, and Taito management had low expectations for Space Invaders after fellow release Blue Shark garnered more attention at a Taito unveiling, with much of its early sales going to Taito’s own game centers and those run by partner companies that wanted to maintain a good relationship with the company but predicted the game would bomb. Within a month of its release into arcades in June, however, it was clear Taito had a major hit on its hands. Enter the Invader Boom.

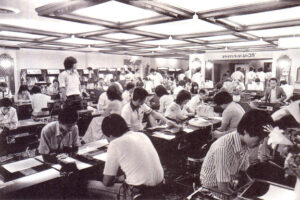

Breakout was a hit in Japan, but nothing quite compared to Space Invaders up to that point. The recently introduced cocktail table form factor – popularized by Taito’s 1977 Breakout clone TT Block – meant the game could fit right into bathhouses, cafes, restaurants and other shops that would likely not install upright cabinets, and it quickly proliferated across the country. Arcades and venues featuring nothing but Space Invaders became known as Invader Houses, and Taito faced an array of bootleggers copying and selling their game as the company struggled to fill orders. Taito made licensing agreements with several other companies to produce official units and clones of the game to help meet demand without leaving operators to turn towards these unofficial bootlegs, and even sued in what would become a landmark case establishing that software was indeed copyrightable in Japan. There were reports of localized coin shortages in some areas, leading members of the Japanese Diet to negotiate with Taito over getting the machines emptied and coins back into circulation. The first video game strategy guide to come out of Japan was for Space Invaders, and the game was one of the first where entire strategies would develop to try and land the high score, including clearing out columns and counting shots to always score 300 points on UFOs, to the “wall of death” or “Nagoya Attack” strategy, first developed in Nagoya, where it was discovered that the aliens couldn’t shoot the player if they’re on the very lowest line. This would lead to players drawing out each wave to catch the maximum number of UFOs, only killing the bulk of the invaders once they came down to the final row. Nishikado was concerned that such a massive bug would’ve cost him his job given the number of Space Invaders units that had been shipped out by the time it was discovered, but ultimately since it continued making money no one at Taito gave him a hard time over it. Additionally, players discovered an unintentional “rainbow” secret in the game, where leaving one of the invaders from the bottom two rows for last would cause it to leave a graphical trail on screen. Ironically, despite its success, Nishikado has indicated that he never actually set foot inside an Invader House, did not think too greatly on its popularity, and was largely hung up on the graphical limitations the board he used had to contend with.

By the end of 1978, Taito had itself sold 100,000 units, and sales would continue to be strong over the following few years, with an estimated 300,000 official and clone units installed in 70,000 locations across the country by September 1979 – two thirds of which were in tea rooms. Mere months after the original’s release, Taito issued a color version, which acknowledged the growing player skill with the game by adding an extra digit to the score counter. This too was developed by Nishikado, who said it took about two weeks to work out the color circuitry. 1979 saw the Invader Boom peak in the middle of the year, when a new initiative came from the All Japan Amusement Park coin-op industry association to cool the market amidst a moral panic. Invader Houses had gained a reputation for being seedy places and the industry wanted to make sure it didn’t get regulated by the government; as such the association purposely dampened enthusiasm for the game by implementing new restrictions on when and how kids and teens could play coin-op machines and staffing requirements for locations. Nevertheless, late in the year Taito brought out a sequel, Space Invaders Part II. This follow-up added cutscenes, visual flourishes, bonus points for shooting the final invader during the now-intentional “rainbow” glitch, and new enemies – including an unused fourth invader Nishikado had intended for the original – but otherwise followed the original game’s core game loop with enough tweaks that the same high-scoring strategies don’t quite work as smoothly. It never hit the highs of the original game, but nevertheless moved its share of units.

Even as things were slowing down in Japan, however, Taito’s game would prove to have some serious legs around the globe. Taito America’s operation was small, but a location test in Colorado proved it would be a hit. Taito ended up licensing the game to Bally-Midway for distribution in North America and Europe due to its own limitations in producing ample copies. While the industry press was not highly impressed, Midway produced and sold nearly 65,000 units of the game, making it the biggest selling coin-op game since the 1930s and one that strained their production capabilities. The game’s popularity in Hawaii, where the Invader House phenomenon spread from Japan, is particularly notable. The island state had its own Invader Houses, called Invader Wars, with machines being brought in from the US mainland and imported from Japan. While the game didn’t reach quite the same levels of mania in the west as it did in Japan, it was nevertheless a massive hit generally considered to have ushered in the “Golden Age” of arcade games, thanks to its sophisticated design and graphical work, which set a new standard that game companies across the globe would strive to surpass Space Invaders.

It was within this context that interest in a home version began to grow, and at Atari that was attributable to Rick Maurer. A consumer division software developer recently hired in from Fairchild, Maurer had written Hangman, Pinball Challenge and Pro Football prior to the company’s consumer division closing due to the collapse of the digital watch market. In the 1997 Stella at 20 documentary, Maurer said he entered Atari at a time when the programmers were debating whether it was better to create original games or make conversions of arcade titles. He said the majority felt original games were better, but he was struck by inspiration while searching arcades for a game idea when he came across Space Invaders. Taito’s game completely wowed him, in particular its sound, and he decided to start writing a home version. Management was fine with him pursuing the game and after about four or five months, he’d written an initial version that, while fun, seemed uninteresting to other Atari staffers – who he added never seemed to talk about even the arcade version. Maurer was struggling with severe flickering on the screen, and figuring the game had no real interest, put down the project to work on his other VCS game, Maze Craze.

After several months of working on that project, at some point in 1979 he learned that management had just then discovered how much money Space Invaders was raking in at American arcades. A high level Warner executive working at the office of the company’s president, Manny Gerard, saw the lines of Atari employees waiting to play the arcade cabinet in Atari’s test labs and pushed Atari CEO Ray Kassar to get the home rights no matter what. Separately, the Japanese licensed distributor for the VCS, Epoch, requested Atari make a Space Invaders cartridge for the VCS as it was struggling to move consoles at the time. Regardless of which of these activities led to Atari securing the home rights, the company successfully negotiated with Taito to bring an official take on the arcade phenomenon to the residential space.

This was a first for Atari, or indeed any home video game maker: prior to this all the arcade conversions were either unlicensed clones like Outlaw, or from in-house products like Sky Diver. Actually licensing someone else’s arcade game for a home version simply had never come up at any of the existing home game divisions at the time, which led to some confusion (as we’ll see later). Given that Maurer had already started on the game, he was put back to work on it. The license didn’t mean that he had any additional assistance developing the game, however. Maurer said he didn’t get any code listings or documentation from Taito for his home version, so all he could really do to inform it was to watch and play the arcade game and approximate the core experience as best he could.

With the break, Maurer was able to resolve the flicker issues quickly. Maurer also loved the idea of game variations: in part because it was a way to have a backup plan in case one version is simply better than the others, and as a way to keep players interested and challenged even after they’d mastered the base game. For Space Invaders, he filled the game out with variations upon variations for both one and two players. In all the game would ship with 112 of them, so many that he had to add in a trick to fast-scroll through them all by holding down the select and reset switches.

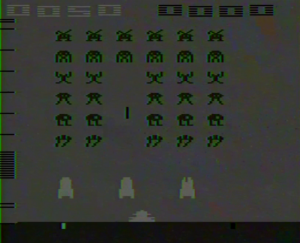

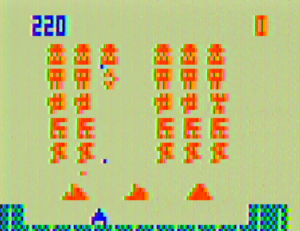

Finally, since Maurer was dealing with different hardware restrictions, he recognized his game couldn’t be an exact copy. With a lower screen resolution, the number of invaders was reduced from 55 to 36, and the sprites had to be redrawn. At first Maurer requested the company’s art staff take a shot at it, but after not hearing back, he ended up drawing the aliens out on graph paper and implementing them himself. The rows of invaders used the VCS’s lack of a frame buffer to Maurer’s advantage; while the VCS can typically only draw two sprites on screen at a time, once the electron gun has passed a certain point it was possible to draw in another sprite in the same row. A similar method was used to draw the playing cards in Blackjack, and it worked well for Space invaders. The sound design was a particular point Maurer was focused on, given how enamored he was with the arcade game’s aural soundscape. Recognizing that the VCS was incapable of matching up to the custom arcade hardware Nishikado used, Maurer did the best he could to approximate the sound effects of the invaders, which went from a deep, imposing bassline to a staccato, inexorable march. Maurer’s game ended up sitting at 7 kilobytes of space, and he then spent about three months pecking away, byte by byte, to cut down the game’s size to fit onto a 4k cartridge. But finally it was ready, and Atari had a big marketing blitz ready to roll for when the game hit store shelves in March 1980, with it as the centerpiece of their holiday ad campaign the following fall.

How’s the game itself, though? Simply speaking, it’s a real masterpiece of its day. The core game doesn’t include the variable point values for the mystery ship, nor does the Nagoya Attack strategy work, but the core loop of the invaders pressing down on the player until their final victory is intact. The game may be easier than the arcade original at its default settings, but it’s still difficult to keep the battle alive past a few waves. And that’s only looking at the initial mode. Maurer added in variants where the defensive shields constantly move back and forth, ones where the alien’s shots drop far quicker than usual, ones where their shots will move erratically back and forth, making them harder to dodge, and most deviously, game types where the invaders are invisible unless one of them is shot. Maurer made sure that there’s a variant that mixes and matches each and every one of these. In all, you get 16 single player options of varying complexity, and then multiple two-player modes that include all 16 of these variants. There’s a standard two-player mode where the players alternate turns, a mode where they compete at the same time, and ones where they compete at the same time but have to alternate shots. Maurer also added co-op games: one where the players control one cannon and move it left or right, respectively, another where they alternate control after each shot, and a final version where one player controls the cannon and the other shoots. Flipping the difficulty switches will adjust the size of the player’s cannon from a slim size that fits neatly under a shield to a stretched version that makes dodging alien fire much more difficult. And finally, the game includes an unofficial variant when you hold down the reset switch when turning on the game: this results in your cannon being able to fire two shots on screen at once and makes clearing out invaders a breeze. It’s incredible that Maurer came up with these many variations and got them all to fit in his already overstuffed cart, but they’re what really gives VCS Space Invaders its character. While the base game is a solid experience, it gets absolutely wild mashing up the fast bullets with the erratic shots, and any mode with the invisible invaders is a real challenge of your ability to recognize how quickly the invaders move across the screen. The strategy of firing open a hole in the line of invaders to pick off mystery ships is still largely intact here, even though they’re worth a steady 200 points (or 100 in a couple of the two player modes). Without the Nagoya Attack strategy the player generally has to stop UFO hunting early to survive the level, but it’s still a good approximation of the arcade.

The two player options are noteworthy themselves for featuring early examples of co-op play. The alternating turns variant is pretty standard stuff, but having both players working together to clear the screen of invaders is a rather unique experience for the time. The alternating control and split control options work better here than they did in John Dunn’s Superman game, and having to work in tandem adds a whole new layer of difficulty to the game – especially if other variations are in play.

And while Maurer’s alien designs aren’t as instantly recognizable in 2020 as Nishikado’s originals, they have their own funky charm and work well within the resolution limits he faced. Everything is recognizable for what it is, and for anyone who came up with a VCS in the house, the audio cues and the game’s visual appearance are iconic in their own right. Regardless of the differences from the arcade, the game was praised in contemporary reviews. Bill Kunkel and Arnie Katz looked at the game in the October 1980 Video magazine as part of a trio of space-themed games they felt were entering new ground and setting new standards of excellence in game design. For Space Invaders in particular, they noted it closely resembled the arcade game – enough so that the default gametype was their preference, as diehard fans of the arcade original. The December 14, 1980 Muncie Star Press ran a review of what author Rick Teverbaugh referred to as one of the most popular Christmas purchases of the season. After running down the variations in the cartridge, Teverbaugh said it was the best example of how a home video game can take up an entire evening without repeating a single program. The game was also praised as the best home video game available in Craig Kubey’s 1982 The Winners Book of Video Games, wherein the author noted that while it wasn’t identical to the arcade game, it still played well and a number of the same strategies and skills carried over.

As mentioned, Atari had an ad blitz prepared for the VCS in the fall of 1980 with Space Invaders as its star. The game got its own TV commercial, print ads, and a heavily promoted National Space Invaders competition featuring qualifiers across the US and finals in New York. It was ultimately won by future game developer Rebecca Heineman, who took home her own Missile Command arcade machine. Atari would host another competition the following year, albeit with a broader scope than just Space Invaders. While it’s difficult to say how much this campaign affected sales of the almost-immediately popular VCS game, Atari itself estimated that the game sold more than 1 million copies in 1980, the first VCS game – or indeed, any home cartridge – to do so. Internal documentation suggests it sold 1.3 million copies in 1980, with another 2.9 million in 1981 and 1.3 million in 1982… and an additional 435,353 copies in 1983, when the market was particularly soft.

Space Invaders continued to be a steady, strong seller for Atari right up to the end. Even in the late 80s during Atari Corporation’s years with the platform, Space Invaders sold consistently, with a total of 161,000 units sold between 1986 and 1990 both domestically and abroad. While its sales didn’t best Atari’s newer games – or unexpectedly, Pole Position – from 1986 through 1988, sales were routinely healthy in this period as well. All told, Atari sold somewhere in the vicinity of 6.2 million copies over the course of the system’s life, making Space Invaders the second-best-selling game for the VCS behind Pac-Man and one of the best-selling games of the 1980s period.

The cartridge is credited for quadrupling sales of the VCS as the first “killer app” and causing Atari to run away from its competition on the market, as people bought VCS units just to play Space Invaders. This in turn had the knock-on effect of allowing subsequent VCS games to sell more copies, and within a few years games like Pac-Man, Frogger and Pitfall! would reach the same million+ seller heights as Space Invaders. In the fall of 1982 Sears would flat out replace the pack-in title for their Telegames-branded VCS, swapping Target Fun out for Space Invaders.

Maurer didn’t see much of the spoils of Atari’s success with his game, earning a $3,000 bonus for his work. Dennis Koble, in a 2017 interview on the Atari Compendium, argues that Maurer’s relatively paltry bonus directly lead to developers eventually getting decent royalty checks from publishers of their games. Other than Maze Craze, Maurer would not complete any other VCS games; he was then shifted over to the arcade division to work on Space Duel before eventually leaving Atari to work in mathematics, which he had a degree in. Maurer would return to game development in the 1990s, but seems to have gone off the grid since the late 2000s. Nevertheless, his ability to design and code games on limited hardware earned him a great deal of praise over the years. Maurer took care to give a large share of credit to his VCS conversion’s success to Nishikado, who he said did the hard work of designing the game in the first place.

Given the massive success of the arcade game – and the improperly protected copyright on Space Invaders – clones in everything but name popped up on home consoles outside of Atari’s. The earliest would be for the Bally Professional Arcade, where the initial run of the carts even carried the Space Invaders name – the company seemingly thought they had both the arcade and console rights until Atari’s announcement that it had the name rights as well, forcing the change to Astro Battle. A similar situation appears to have played out regarding its Galaxian home port, released as Galactic Invasion after Atari announced it had secured home rights directly from Namco. This first release did seem to move at least one console – Bally indie developer Mike White remarked that he bought his unit in January 1980 after seeing Space Invaders was available for it. This version features 32 invaders, four barriers, and plays reasonably similarly to the arcade game, with some odd changes: the mystery ship now emerges randomly rather than on a consistent timer, and the invaders themselves will begin spawning almost directly above your cannon by the fourth wave, making this a particularly challenging rendition.

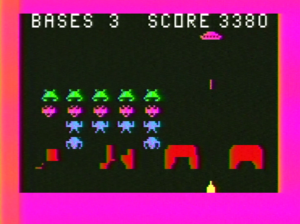

The Intellivision plays host to Space Armada, with 32 aliens and three bunkers. Developed at contracted studio APh upon Mattel’s realization that the gameplay of Space Invaders wasn’t copyrighted, this program is actually more impressive than it lets on. The Intellivision hardware is incapable of moving more than eight objects on screen at a given time, but developers John Brooks and Chris Hawley got around this using what’s called GRAM sequencing: essentially animating background tiles in such a way that makes it appear that there are more enemies active than there actually are. This version’s chunky, partially background-object sprites leave little room to maneuver, but its unique features allow it to transcend being a lesser Invaders clone. While it starts out as a fairly straightforward take on Taito’s game, Space Armada ups the ante as you get further. The aliens begin dropping new kinds of missiles, including guided ones that follow you around, missiles that have splash damage when they hit the ground, and a star-shaped attack that follows you around in such a way that you really need to use the barriers to protect yourself from it. The aliens themselves will also turn invisible in certain waves, only becoming visible at random times. Shooting UFOs will not only earn you a random point value, but it also will restore the most damaged bunker on screen, a slight accommodation to the player given the firepower advantages the aliens get. That said, if you get far enough, the UFOs will begin making their own attack runs, outright stealing your barriers and leaving you exposed. To counter the offensive prowess of the attackers, you in turn start with six lives and gain a new one every time you finish a wave. Additionally, Space Armada includes a practice mode that allows you to try out a level that you’ve lost on repeatedly to get a better handle on it so that you can stretch those lives out further. This is a pretty handy concession for a game beefed up for a console audience, and while it’s hard to say this is better than Atari’s game, but it’s unique enough to have its own flavor. Space Armada comes across as significantly more aggressive a game than the measured, shot-counting approach to high scores in Nishikado’s version, further setting itself apart. Given how hot space games were and how little competition there was for arcade action on the Intellivision, this proved to be one of Mattel’s best-selling games based on internal documentation, moving 931,100 copies to retailers by the end of June 1983.

Also published in 1980, Alien Invaders — Plus! for the Magnavox Odyssey2 introduces several twists on the formula in its own right. Barriers are now indestructible, and the invaders don’t progress down the screen per se – rather, they are firing from behind their own barriers at the player while slowly moving back and forth and down the screen. Losing your base leaves you as a lone human who can equip a barrier into a new base. Every time you lose all your bases or the invaders are all wiped out, either you or the computer scores a point; the first side to 10 points wins. The mothership is replaced with the Merciless Monstroth, a tentacled creature that will take pot shots and, once all your shields are gone, will drop down to the bottom of the screen to take you out while you’re relatively defenseless. The Monstroth will also make its attack run once all the aliens have been eliminated, making it smart to try and take it out and then blast the last alien before it has a chance to respawn and dive at you. This is an interesting take on Space Invaders, as shooting either an enemy cannon or the alien themselves will silence that gun, but it loses some of the tension of the arcade game, particularly with every round being functionally the same and the invaders never really hitting the ground.

In late 1981, Zircon published the final Channel F game, Alien Invasion. This game has 35 invaders and three bases, and was developed by former Fairchild programmer Brad Reid-Selth on speculation for the company. Inspired very directly by the VCS Space Invaders conversion, Reid-Selth remarked he was under severe schedule constraints and hardware limitations to develop a game that played better on the VCS to begin with; he and Zircon ended up losing money on it and the sour experience drove him out of the game industry. That said, it does play well and a few of the same options as the VCS game make their way here, including the alternating and simultaneous two-player modes. Reid-Selth added in several variations that mix up the number of shots the aliens can have onscreen at once between the standard two and a trickier four, as well as how many shots the player can fire at once – either one or two. It may have been a market failure, but it’s a strong note for the Channel F to go out on, and a pretty fun, if not particularly unique, clone. Reid-Selth did sneak an easter egg into his game that displayed his name before the action starts, and replaces the UFO with a duck.

The final MP1000 game is also an Invaders clone. Known as Space Destroyers, the game was initially published on cassette for APF’s Imagination Machine computer expansion in November 1980 before being rereleased on a cartridge for the company’s standalone console in 1981, two years after the previous batch of MP1000 games came out. This is a remarkably accurate conversion of the arcade original, with the appropriate number of invaders and shields. It even attempts to match the design of the aliens and the pace of the arcade game. MP1000 engineer Ed Smith called it his favorite game on the platform, and certainly it’s a highlight, looking and playing very closely to the Taito original.

And when Emerson released the US version of Philips’ Signetics-based console, it launched with 20 games, including a Space Invaders clone called Alien Invaders. This takes its own twists on the formula by pitting you against 70 invaders and a timer. You have 500 seconds to clear out the invaders and as many UFOs as possible, but they don’t necessarily move down the screen when they hit an edge. Instead, they will just wrap around, and only speed up and descend based on how much time is left on the clock. If you’re still alive at the end of the 500 seconds, your score is tallied up with bonus points for remaining laser bases. It’s a strange version and the color scheme is rather garish, but the developers attempted to put their own spin on what was in 1982 a fairly old game concept. I don’t know who would have been necessarily more excited for Alien Invaders against Maurer’s take, but I’d consider it a fairly worthwhile effort.

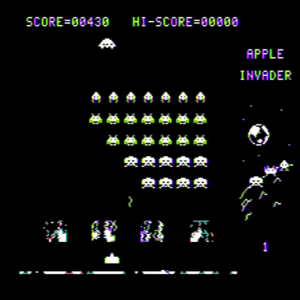

Space Invaders was also a popular choice for microcomputer platforms. There are simply way too many of these for me to be even remotely comprehensive, but if it’s a computer system from the late 70s through the 1980s, odds are it’s got at least one Space Invaders clone floating around that was relatively popular. Perhaps the most notable of these was Super Invader, also known as Apple Invader. This was a surprisingly accurate take on the arcade game written for the Apple II by Japanese programmer M. Hata and published by Creative Computing, where it quickly became itself known as one of the best-selling games on the platform. While other computer clones may not has been as true to the original game, Super Invader shows the degree of interest in Space Invaders stretched even into the often-siloed home computer market.

Recognizing the success on their hands from the Space Invaders license, Atari even made plans to produce and sell a handheld version of the game, though this never did reach stores. Atari planned on producing a version of Space Invaders for its Cosmos holographic game system, but this too was shelved when the product was canceled.

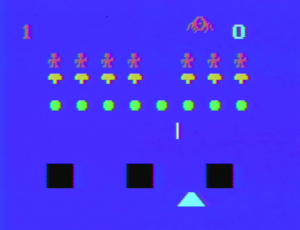

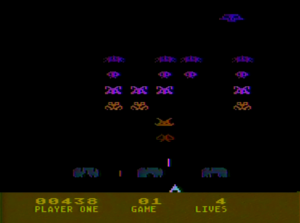

But Atari did publish a truly strange take on their 8-bit computer line in 1980. Developed by Rob Fulop, this features some very clear departures from the arcade original: there are no barriers on the field, and the field of 48 invaders themselves slowly march out of a rocket off to the side at the start of each round. In an interview with Paleotronic, Fulop indicated that he had decided to work on this version without any prompting from the company even though by that point it was known that Atari had the home rights. He also decided on his own not to just “copy” the original coin-op release as he had done so with his previous work, a Night Driver conversion to the VCS. He was pleased with his changes in the moment, but said he felt like a moron after marketing asked him why he didn’t just copy the arcade game since that’s what buyers would be expecting; this experience led to him working out a conversion of Missile Command to the VCS that matches its inspiration much more closely.

The 8-bit Space Invaders also served as the basis for the 5200 console release that debuted in 1982, albeit with extensive changes and tweaks by developer Eric Manghise and artist Marilyn Churchill. Some of these make it a little more like the arcade game, such as adding barriers and removing the introductory march seen in Fulop’s game. Churchill remarked in a 2009 interview that Space Invaders for the 5200 showcased a technique she’d developed called “matrix animation,” where she developed a looping animation and placed it on a grid, with slightly different animations adjacent to it; Manghise set the game program to pull from adjacent squares on this grid, randomly stepping up or down on it to produce an unpredictable animation array as the 48 invaders march along. Despite the more advanced hardware, however, neither the 5200 or 8-bit takes quite nail the right speed and rhythm that Maurer managed with his version, though, despite being built on more capable hardware.

Direct clones aside, however, Space Invaders casts a long shadow on both arcade and home gaming. The game’s soundscape and characters have been an iconic part of Japan’s game landscape since its release, and Taito has not been shy about selling Invaders merchandise and games both new and old over the decades – from several arcade sequels to Taito’s own Space Invaders’ Famicom conversion in 1985, all the way to 2018’s Space Invaders Gigamax installation. The aliens themselves now serve as the company’s de facto mascots, decorating merchandise, their arcades and making cameos in other games. Midway would also continue to ride their Space Invaders license for a few more years in the arcades, bringing Part II to the West as Deluxe Space Invaders, including an Invaders-themed level in Jamie Fenton’s GORF arcade game. and its parent company Bally even produced a Space Invaders pinball machine that was a big hit in its own right.

But Space Invaders’ aftermath goes beyond that. In Japan, the end of the Invader Boom forced other companies that had been contracted to help produce Space Invaders machines to start pumping out new games simply to keep afloat – resulting in obscurities like Cutie Q and hits like Galaxian. And more broadly, without Space Invaders introducing the fixed-screen shooter genre – or STGs, or shmups, or whatever you want to call them – you wouldn’t see games like Scramble and Xevious. These games and their contemporaries laid the groundwork for the horizontal and vertical shooter genres, which would go on to be a major pillar of the game market in the late 80s and early 90s. The round-based game systems and high-score chase popularized by the original Space Invaders arcade game would continue to be a part of video game design even up to today – while it isn’t the first arcade game to feature high scores, rounds or even shooting, it absolutely popularized and cemented these features. Space Invaders is considered one of the most important games in the industry’s history, and it’s hard to argue against that reading.

At home, the success of Rick Maurer’s conversion led Atari and its competitors to largely end that initial argument over arcade conversions versus original titles, and recognize the strength of licensed arcade ports to consoles and computers. This lead to conversions both famous and infamous of games like Burgertime, Frogger, Donkey Kong and Pac-Man that were originally written by arcade-centric companies with no internal home game development arrangements. It also set a standard of targeting the way an arcade game felt and the major components of its gameplay loop over trying to match it exactly, a baseline nearly every arcade to VCS conversion would follow to varying levels of success. Space Invaders broadly brought with it the popularization of the modern fixed-screen shooting game genre, which would dominate both arcades and home games from here on out – it’s not an exaggeration to say that within a couple years, a large chunk of games coming out on the VCS will be shooting games either directly aping Space Invaders or one of the many arcade games inspired by its formula. Without Taito’s Space Invaders, you wouldn’t get Namco’s Galaxian or Xevious; without either game you wouldn’t have gotten VCS games like Demon Attack and Stampede.

More broadly, Maurer’s Space Invaders is the game that made the VCS the hottest piece of entertainment in its day, and inadvertently led to its downfall. Atari was a fairly small operation in the 1970s, but after Space Invaders came out it had to rapidly scale up its operations to accommodate demand. This led to the company failing to fulfill all its orders in 1980 and 1981, which retailers and distributors dealt with by over-ordering product to receive approximately the amount they actually wanted. This in turn led to the glut of game copies that hit stores in 1982 when production finally caught up, forcing down prices on games both old and new and limiting the reach and availability of newer titles as retailers tried to clear out this old stock. The “Crash of 1983” couldn’t have happened without Space Invaders setting the stage back in 1980.

Maurer’s own game would prove to be a popular target of graphical hacks in the age of emulation, but Atari did their own in-house hack in 1982, known as Pepsi Invaders. This was a special gift for Coca Cola executives at the 1983 Coca Cola Sales Convention that tweaked the alien and UFO graphics and inserted infinite lives and a time limit. It’s a deeply weird title and today a pretty hot collectible on the VCS aftermarket, as only 125 copies were ever produced.

Beyond hacks, homebrewers have come up with a variety of their own takes on Space Invaders on the VCS too with bids to match up with the arcade game a bit better than Maurer did going back to 1997. But while these versions may strive for a greater degree of arcade accuracy, there is something about Maurer’s game that makes it something special, almost timeless. Maybe it’s the variations, the soundscape, the pace of the game, or just the timing of its release. Even though it’s not readily available on modern collections due to rights issues, it’s hard to argue that for Americans of a certain age, this IS not only the definitive Space Invaders, but one of the most iconic games on the VCS.

Sources:

Stella at 20 materials, Glenn Saunders, 1997

Reminiscing with Richard Maurer, James Hague, dadgum.com, Jan. 5 1999

Once Upon Atari, Howard Scott Warshaw, 2003

The Fairchild Channel F Panel, Classic Gaming Expo 2004

The Atari Programmers Panel, Classic Gaming Expo 2004

The Atari Programmers Panel, Classic Gaming Expo 2005

Space Invaders – Comment Tomohiro Nishikado a donné naissance au jeu vidéo Japonais, Florent Gorges, 2018

Space Invaders Invincible Collection Official Book, 2021

Tomohiro Nishikado – 2000 Developer interview, shmuplations.com

Space Invaders – 30th Anniversary Developer Interview, shmuplations.com

Early Arcade Classics: 1985-87 Interviews, shmuplations.com, original from BEEP!

Epoch and the Cassette Vision, shmuplations.com, original from Game Odyssey

Space Invaders Invincible Collection: Creator Interview, onemillionpower.com, original from Famitsu

Once Again Asking the Father of Space Invaders About its Creation, onemillionpower.com, original from Space Invaders Materials Collection

All in Color for a Quarter, Keith Smith, unpublished manuscript, 2016

Space Armada, Blueskyrangers.com

Cartridge Shipment Memo, Mattel Electronics dated Nov. 30, 1983

Brad Reid-Selth, correspondence with Fredric Blåholtz, May 2001 (and shared with the author)

The Winners Book of Video Games, Craig Kubey, 1982

How to Attack Invaders, 1979

An Interview with Atari 2600 developer and Imagic Co-Founder Rob Fulop, Paleotronic, March 29 2019

Marilyn Churchill interview, Scott Stilphen, Ataricompendium, 2009

Dennis Koble interview, Scott Stilphen, Ataricompendium, 2017

Interview: Tom McHugh, Ethan Johnson, thehistoryofhowweplay, April 3 2018

Bob Ogdon, interview with the author, Aug. 17 2020

Hand-held games top $60, Merchandising, February 1981

Ed Smith, Black Video Game and Computer Pioneer, Benj Edwards, vintagecomputing, Feb. 22 2017

Release date sources:

Space Invaders (VCS), March 1980: Madison State Journal, February 28 1980; Washington Post, March 14 1980; Washington Post, March 16 1980; Merchandising, June 1980; Chicago Tribune, March 23 1980; Washington Post, March 28 1980; Honolulu Star Bulletin, April 3 1980; Plain Dealer, April 9 1980

Space Invaders (Atari 8-bit), October 1980: Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, Oct. 19 1980; Detroit Free Press, Dec. 13 1980

Space Invaders (5200), October 1982: Computer Entertainer, September 1982

Space Invaders/Astro Battle (Bally Arcade), October 1979: Daily Herald Suburban Chicago, December 10 1979; Arcadian, October 31 1979; Arcadian, January 15 1980

Space Destroyers (MP1000), June 1981: Akron Beacon Journal, June 7 1981; Montreal Gazette, September 19 1981; Ottawa Citizen, November 20 1981, Windsor Star, December 5 1981

Space Armada (Intellivision), November 1981: Modesto Bee, September 13 1981; Fort Lauderdale News, November 14 1981; Garden City Telegraph, October 3 1980;Blue Sky Rangers game list

Alien Invasion – Plus! (Odyssey2), August 1980: Daily Herald Suburban Chicago, August 8 1980; Santa Ana Orange County Register, October 16 1980; Fort Myers News Press, November 30 1980; Elyria Chronicle Telegram, December 6 1980

Alien Invasion (Channel F), Fall 1981: Zircon sales brochure, Fall 1981

INV+ (VCS), June 11, 2004: Author ErikM’s thread on Atariage.com