Ask someone what they know about Tron, and odds that if they know it at all, it’s probably because of the light cycle sequence. In it, cyclists create walls of light behind them as they move, trying to trap their opponent and cause them to crash. As it happens, that idea didn’t originate with Disney, but dates back to the 1976 Gremlin arcade game Blockade. And as we’ll see, Blockade would find itself cloned time and again, including by Atari for the VCS with Surround.

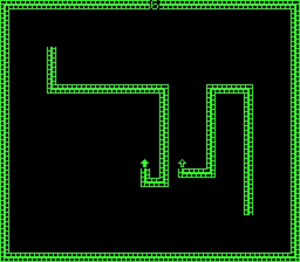

For those unfamiliar with it, Blockade is a two player game where each player moves around the screen, with the ability to turn at 90 degree angles. While moving, they leave a solid line behind them, with the ultimate goal of outlasting their opponent without crashing into a wall – whether that’s the line drawn by their opponent, themselves, or just the exterior of the playfield. Blockade is generally seen as the progenitor of the “Snake” game genre, which was a common sight on computers and consoles for years before gaining popularity thanks to the ubiquitous Nokia cell phone game Snake in the 2000s. According to developer Lane Hauck’s interview with Keith Smith, Blockade developed out of a video circuit he had made to try and convince Gremlin to get into video games. Inspired by the random walk process in physics, wherein a drunk moving randomly in an area with a lamppost will eventually gravitate towards it, he programmed an arrow to move around randomly on screen. This was then tweaked to make it impossible for the arrow to revisit the same square twice, and from there the leap to Blockade was fairly straightforward. The game was an initial hit among operators, garnering 3,000 orders at its first showing, but Gremlin was new to the world of coin-operated video games and struggled to produce enough to meet demand.

Gremlin’s developers weren’t the only ones with this game concept, however. While Blockade was the first game of this sort to actually come out, RCA had developed and location-tested its own similar game called Mines in 1975. Mines differed in that the two player ships have to push a button to begin dropping a trail of mines, but otherwise the game has the same goal of getting your opponent to crash into a wall of obstacles without you doing the same first. Mines was among the games that RCA location-tested in New Jersey and the Bucks County Mall in Pennsylvania in 1975, though the entire arcade project was shelved after RCA’s engineers returned to the test sites to find the machines unplugged and unused, leaving Gremlin to claim the first snake game to market.

Blockade’s fairly simple game design was cloned quickly by Gremlin’s competitors. In 1976, Meadow Games had Bigfoot Bonkers, which added obstacles in the playfield. Midway had a similar game called Checkmate. Ramtek released Barricade in January 1977, which was close enough that Gremlin threatened a lawsuit, dropped when Ramtek agreed to stop selling the game. That same month, Atari produced its own near-exact arcade copy called Dominos, reportedly finished in 13 weeks and available in cabinets allowing up to two- or four-players. Gremlin had a patent on the concept of leaving a trail behind an object in a video game, so it had a strong legal leg to stand on, though, as it turned out, Blockade and its clones were not hugely popular among the public, leading its success to be short lived. Still, that initial rush of interest in Blockade coincided with Atari’s first round of VCS game development, and as such, the company wanted a version of the game for their new VCS platform.

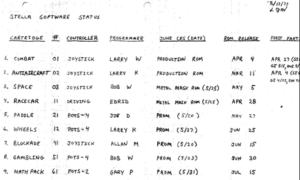

For that, they tapped new hire Alan Miller, who would go on to co-found Activision in 1979 and Accolade in 1984. An electrical engineer, Miller was assigned Surround as his first project, and in an interview with Al Backiel he noted it was based off the same game concept as Blockade and Dominos. Indeed, the head of Atari’s consumer programming crew, Larry Wagner, even had the game marked down as Blockade in his internal notes of games in development.

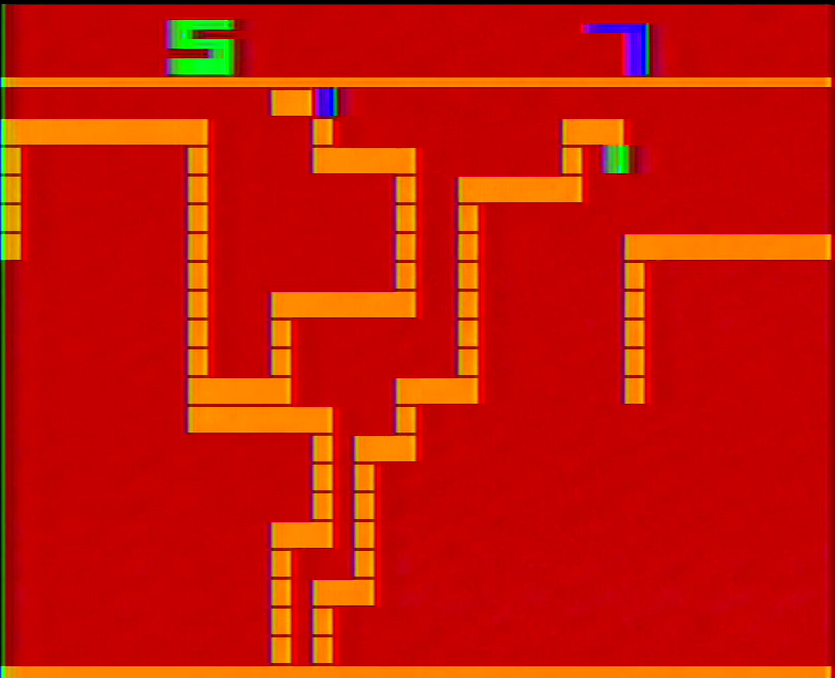

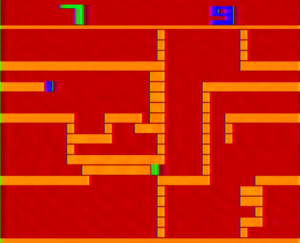

Surround, also released by Sears as Chase, adheres pretty closely to Blockade in its default gametype. Two players, or one player and the computer, square off in an enclosed space that simply by virtue of moving is shrinking. Each player is moving at a constant speed, which can actually up the stress levels as you find yourself slowly being funneled into a death trap, potentially of your own making. Cause your opponent to crash, and you get a point; whoever gets 10 points first wins the game. Matches are over in a matter of minutes, even at the default speed setting that first gametype uses. But this is a VCS game, and as such Miller played with the formula with a series of different variations.

Surround, also released by Sears as Chase, adheres pretty closely to Blockade in its default gametype. Two players, or one player and the computer, square off in an enclosed space that simply by virtue of moving is shrinking. Each player is moving at a constant speed, which can actually up the stress levels as you find yourself slowly being funneled into a death trap, potentially of your own making. Cause your opponent to crash, and you get a point; whoever gets 10 points first wins the game. Matches are over in a matter of minutes, even at the default speed setting that first gametype uses. But this is a VCS game, and as such Miller played with the formula with a series of different variations.

To begin with, several gametypes cause the players to speed up every few seconds. At first this is pretty manageable, but last long enough and it becomes pretty difficult to control without crashing into the rapidly filling screen. A computer opponent is only available for the basic game and the basic game with speedups, so a second player is needed for most of the other options; it’s well worth roping someone in, however. Other options include diagonal movement, which adds a surprising amount of freedom

to escape and entrap your opponents. Gametypes featuring the Erase option play similar to RCA’s Mines in reverse, where you hold down the button on your joystick to stop your trail from forming; this can be helpful if you want to backtrack, avoid what could be a certain death trap for a while, or sneakily want to lure your opponent to their doom. Surround also includes a “wraparound” option that allows players to loop around the sides of the screen. At first blush this would seem like it makes it harder to take down your opponent, but really it just allows for incredibly elaborate traps… and occasionally crashing into your own trail when you skip around to the other side. The game’s various gametypes mix and match these different options, culminating in one that includes all of them at once. The difficulty switches determine whether or not the player can reverse direction 180 degrees – helpful in the erase gametypes, deadly in all the others.

Finally, Surround includes Video Graffiti, a drawing program for one or two players. You essentially just move around the playfield laying track however you’d like – one gametype is essentially an etch-a-sketch that requires all lines to connect, while the other includes the Erase option. Most of Atari’s competitors had some sort of video doodling game in the 1970s: from the Channel F and Studio II to the Bally Professional Arcade and MP1000 – so it’s not terribly surprising that Miller stuck in a similar program on a game where it wouldn’t be much of a space hog. The general reasoning behind these was to promote some form of creativity among users – particularly since the target audience for home games at the time were children – though how successful these early video art programs were is still an open question.

While Atari beat its competitors to the market for a home game based on Blockade, it wasn’t alone for long. In 1978, Bally shipped its Professional Arcade game console, a relative powerhouse compared to what else was on the market. The Professional Arcade featured Checkmate, a version of Midway’s similarly named arcade game for up to four players, built right into the console. Checkmate doesn’t feature all the game variants of Surround, but it is a speedier game off the bat with a pretty good AI. It can even be set up to play itself, which today is used mainly as a testing routine to see if the failure-prone Professional Arcade is working correctly. A couple years later, Mattel released its own clone for the Intellivision platform known as Snafu, perhaps most famous for its jaunty theme song. Bringing it full circle to the arcade, Midway’s 1982 Tron arcade game featured a light cycle stage echoing Blockade – and Surround – closely. Additionally, RCA seemed to have some plans for returning to the genre, as a design document held by the Hagley Museum and Library exists for a Studio III game called Blockout that would have rewarded points based on how long the round lasted and featured a “boost” mechanic that would have sped up your icon at the cost of your maneuverability. At this time, there’s no indication that work got started on the game for the Studio III, though similar game with the same title was written by Steve Houk for the Cosmac VIP computer.

Surround did get high marks in the winter 1979 issue of Video magazine, published in late 1978. The reviewer gave the main Surround gametypes a 9 out of 10, noting that the game can get complex and challenging, with loud and fast sound effects that “keep you on your toes.” They were less effusive about the doodle games, referring to them as a decent substitute for solitaire but otherwise dull. It was also praised in Dick Cowan’s December 1978 column reviewing Atari VCS games, where he found it a game that evoked a lot of laughs and remained fun regardless if you win or lose. Much like most of Atari’s initial offerings, the game stayed in circulation for over a decade, with a final 97 copies getting sold in 1988. Despite the rocky reception to Blockade and its clones in the arcades, today Surround is regarded as one of the highlights of the early days of the VCS, and with good reason. It’s fast-paced, easy to pick up, gets remarkably complicated with its variations, and isn’t really like anything else on the platform. The 1970s releases for the console are frequently overlooked, but Surround is one of the few – alongside some we’ve already seen like Combat, Air Sea Battle, and Indy 500 – that really holds up.

Surround seems to have been released in September of 1977, the last game from the first batch of nine VCS titles. Armed with those nine games, the VCS ended up being reasonably successful in its first year. Industry periodical Weekly Television Digest reported in April 1978 that in 1977, Atari sold around 850,000 thousand consumer game units, with roughly 40 percent – or 340,000 – of those being VCS consoles. While those numbers may not seem too impressive at first glance, they do mean Atari outsold its competitors at Fairchild and RCA within five months of the system’s rollout. Fairchild engineer Jerry Lawson estimated in an Alpex v Parker Bros lawsuit affidavit in 1988 that Fairchild had sold approximately 265,000 Channel F units between November 1976 and the end of 1977, which was also about how many Fairchild had produced in that time frame. The company didn’t abandon the Channel F immediately, but after taking a massive hit from the collapse of the digital watch market (with the company reporting losing $24 million in the consumer products market, according to Weekly Television Digest), Fairchild would sell off the machine and its library to Zircon around late March 1979 before being bought up by Schlumberger that July. Internal sales figures from RCA peg Studio II sales as being between 53,000 and 64,000 units from February 15, 1977 through January 31, 1978, prompting the company to liquidate its remaining stock through Radio Shack and kill plans to sell the Studio III and finish development on the Studio IV. 1977 was a difficult year for the home gaming market in general thanks to chip shortages and inclement weather – and for Atari, manufacturing problems – but nevertheless Atari made it through in prime shape for the nascent programmable market, though the dedicated console market accounted for roughly two-thirds of these.

Fairchild engineer Jerry Lawson estimated in an Alpex v Parker Bros lawsuit affidavit in 1988 that Fairchild had sold approximately 265,000 Channel F units between November 1976 and the end of 1977, which was also about how many Fairchild had produced in that time frame. The company didn’t abandon the Channel F immediately, but after taking a massive hit from the collapse of the digital watch market (with the company reporting losing $24 million in the consumer products market, according to Weekly Television Digest), Fairchild would sell off the machine and its library to Zircon around late March 1979 before being bought up by Schlumberger that July. Internal sales figures from RCA peg Studio II sales as being between 53,000 and 64,000 units from February 15, 1977 through January 31, 1978, prompting the company to liquidate its remaining stock through Radio Shack and kill plans to sell the Studio III and finish development on the Studio IV. 1977 was a difficult year for the home gaming market in general thanks to chip shortages and inclement weather – and for Atari, manufacturing problems – but nevertheless Atari made it through in prime shape for the nascent programmable market, though the dedicated console market accounted for roughly two-thirds of these.

It wouldn’t be until the fall of 1978 before additional games for the VCS would begin shipping out, but in the new year the platform would see a new wave of games as Atari’s programmers gained experience and started getting more creative. Despite the seasonal nature of video game sales at the time, retailers reported cartridges continuing to sell at a steady clip through much of the year, though hardware sales continued to be largely back-loaded. 1978 would also see new competitors and the first market dip in the nascent video game industry, thanks to toymakers and manufacturers being convinced video games were a fad and the general collapse of the dedicated console market. But the VCS was just getting started in its 14 year commercial life and decades of ongoing indie support.

Source:

All in Color for a Quarter, Keith Smith, unpublished manuscript

They Create Worlds: Volume 1, Alex Smith, 305-308, 340-342, 2019

Alan Miller, interview with Al Backiel, 2003

B.J. Call, interview with Alex Magoun, 2003 (Held by the College of New Jersey’s Sarnoff Collection)

The Jerry Lawson Papers, Strong Museum of Play, Box 1/Folder 17

The Joe Weisbecker Papers, Hagley Museum and Library, M&A 875/Folder 18

The Richard Peterson Papers, Hagley Museum and Library, M&A 9/Folder 7

Larry Wagner’s papers, copies provided to author by Wagner

The Sega Arcade Revolution, Ken Horowitz, 21-22, 2018

Weekly Television Digest, April 3 1978; April 10, 1978; April 4 1979

Merchandising, March 1978; April 1978

Release Date sources

Surround, September 1977: Corvallis Gazette Times, October 29 1977

Checkmate, January 1978: Weekly Television Digest, December 19 1977

SNAFU, October 1981: Richardson Daily News, November 26 1981

Anderson Bulletin, January 9 1982

Panama City News Herald, January 13 1982