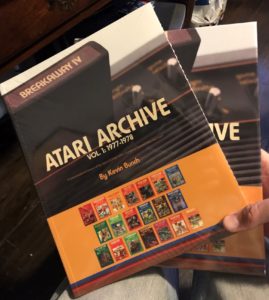

I don’t know how often folks check this website, but I wanted to bring your attention to something I am exceedingly proud of that came out this year: my book!

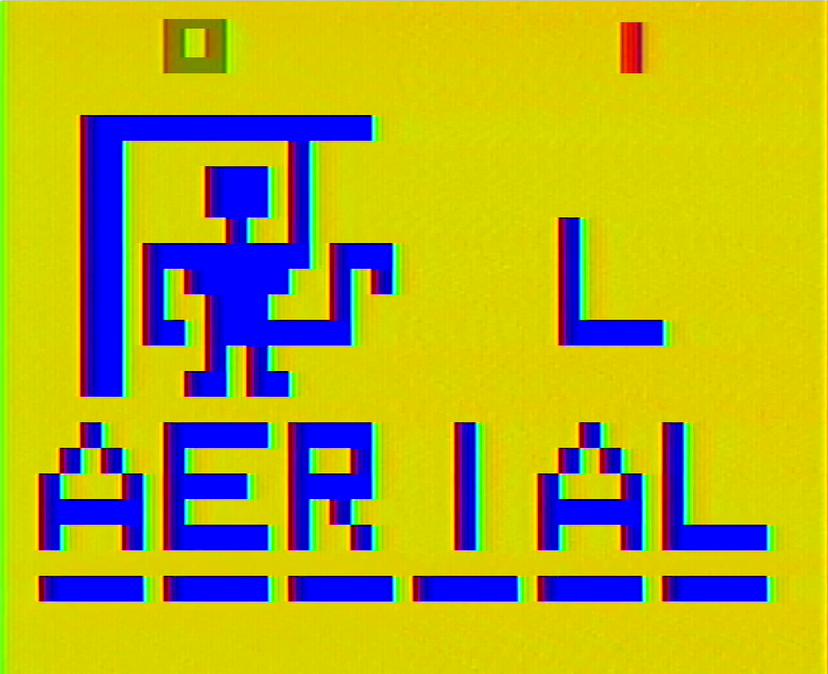

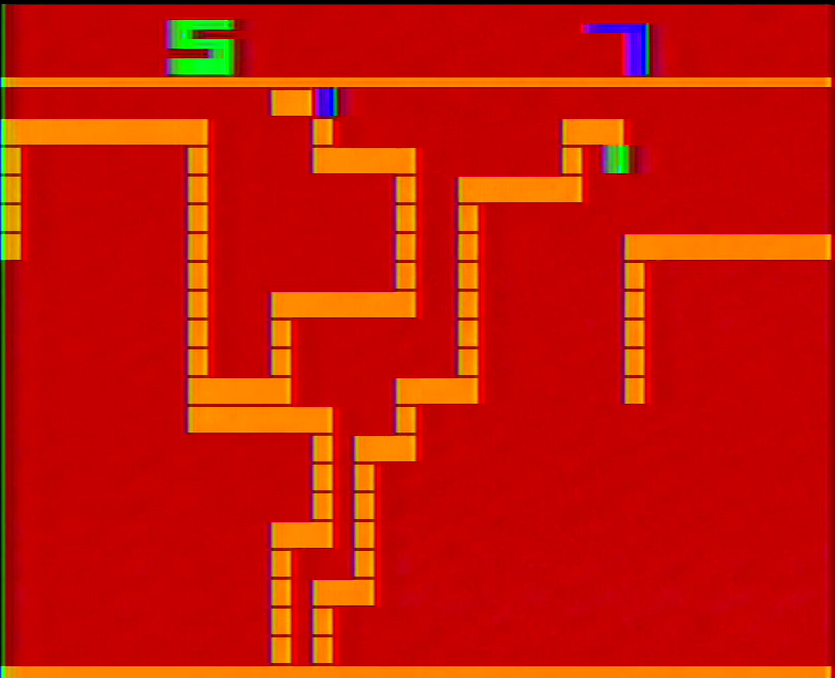

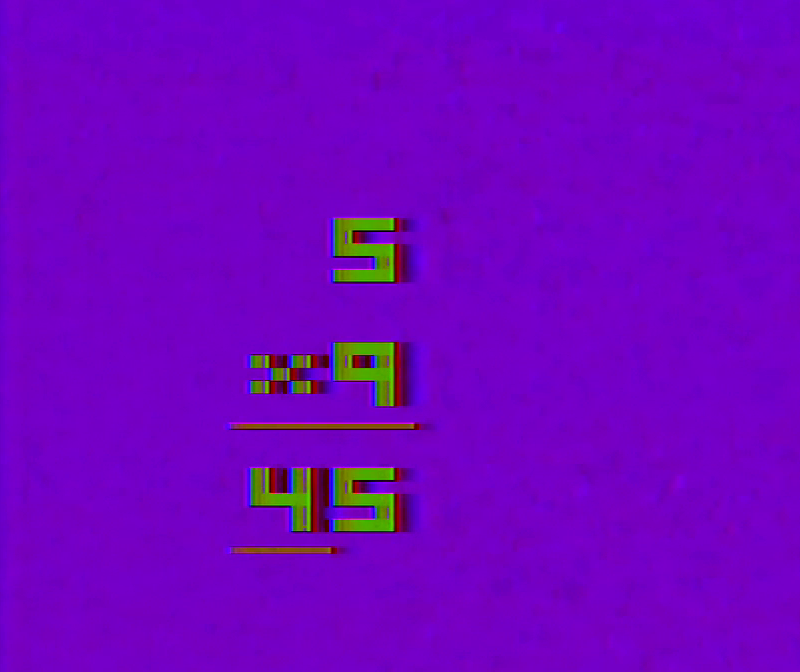

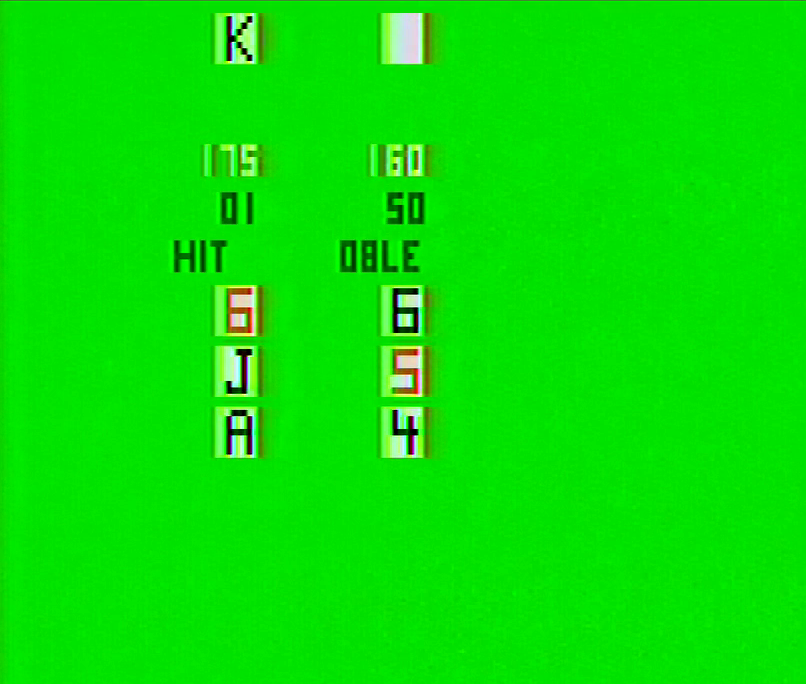

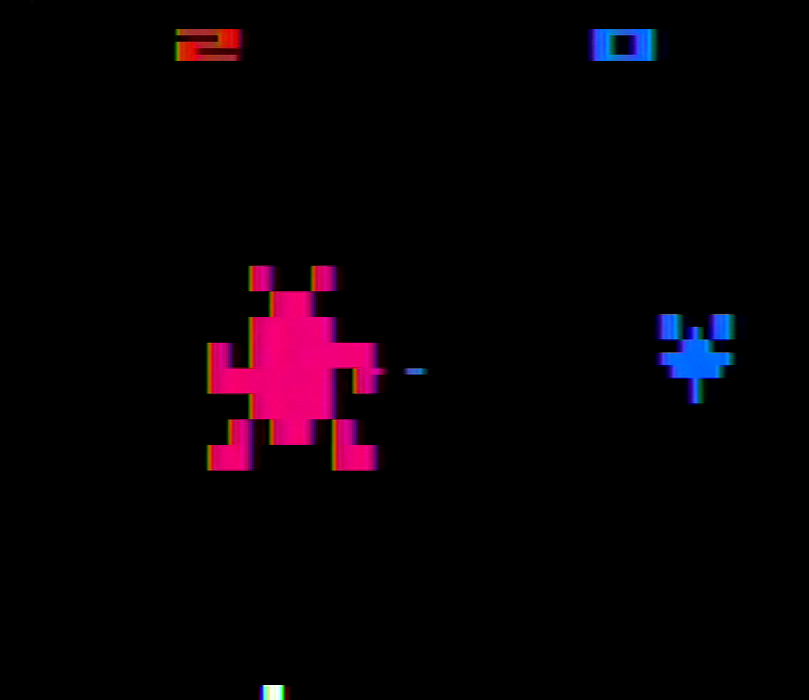

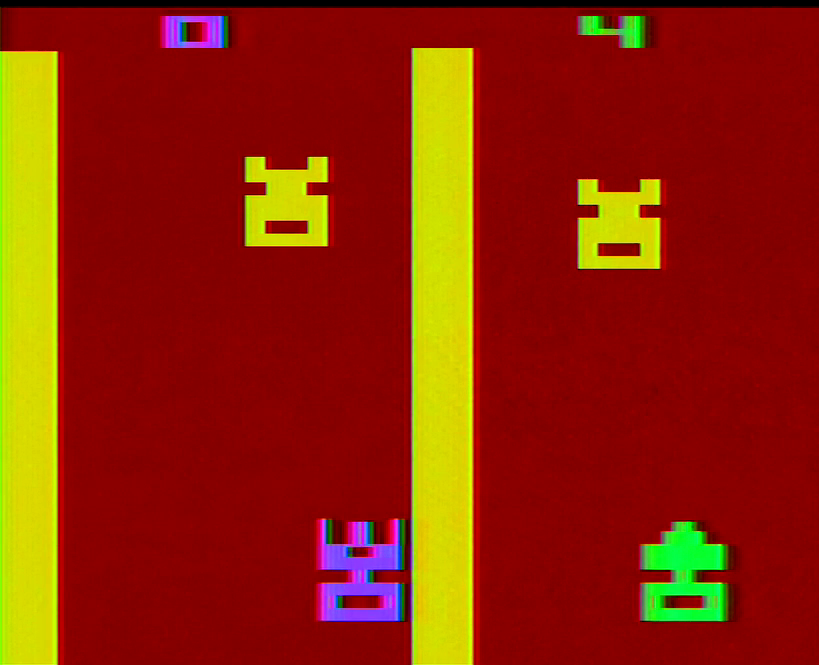

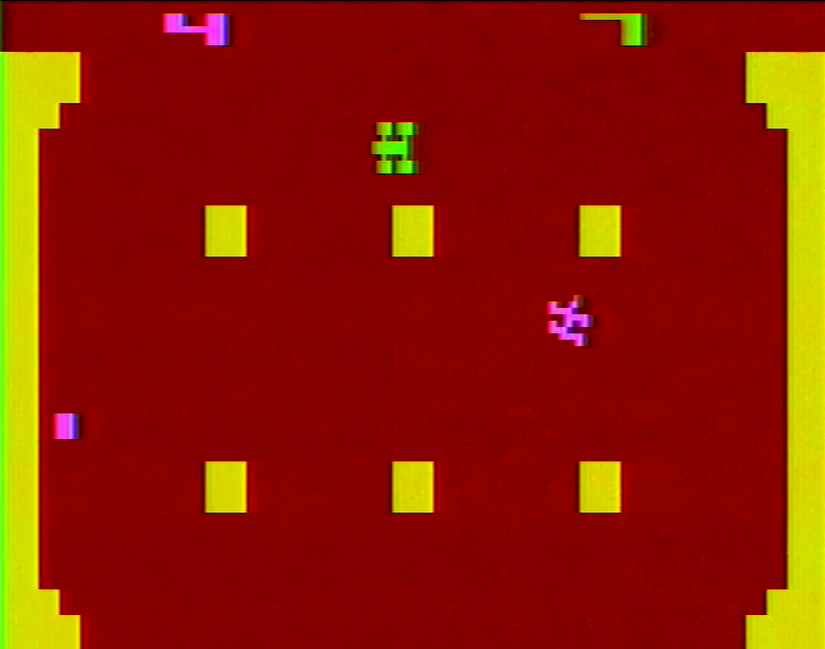

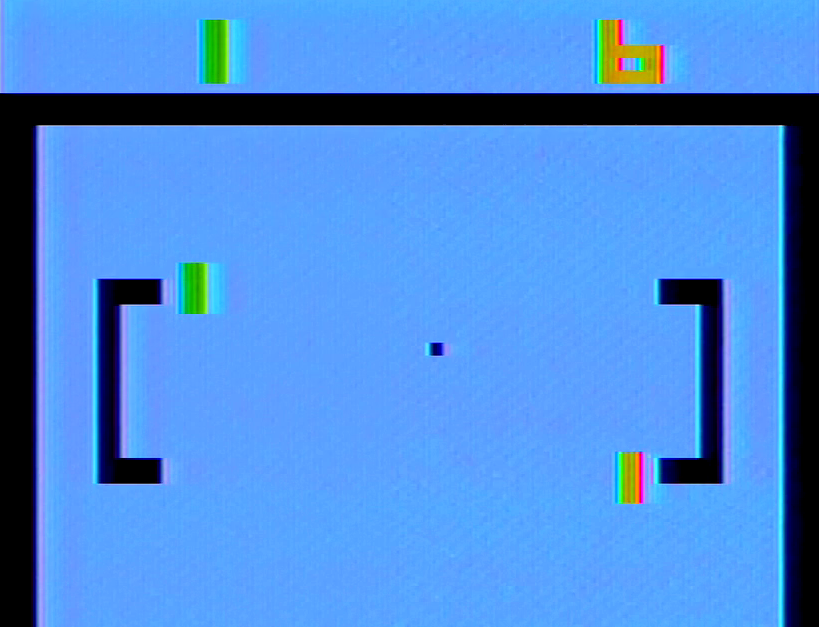

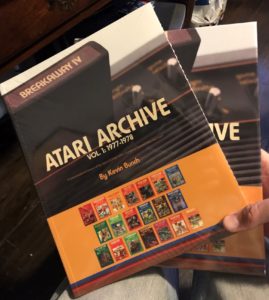

Entitled Atari Archive Vol. 1: 1977-1978, this covers the first two years of the Atari VCS’s life… and then some. If you’ve seen the video series or read this blog, you can guess the format of the book – much of it consists of delving into the history behind each game released in that two-year stint. The chapters are derived from these blog posts, but they aren’t identical, as I was able to come across some details during the writing of this book that I didn’t have putting the blog together.

Entitled Atari Archive Vol. 1: 1977-1978, this covers the first two years of the Atari VCS’s life… and then some. If you’ve seen the video series or read this blog, you can guess the format of the book – much of it consists of delving into the history behind each game released in that two-year stint. The chapters are derived from these blog posts, but they aren’t identical, as I was able to come across some details during the writing of this book that I didn’t have putting the blog together.

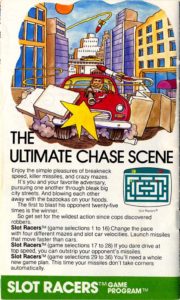

But there’s additional content as well. In order to provide the context that I feel this particular era of video games demands, I also spent time delving into the state of the industry before the VCS’s debut, and dug in deeply on the creation and life of the VCS itself – even interviewing the surviving folks who were intimately involved in its development. There’s a chapter about the FCC’s impact on the video game home market in the 1970s, and chapters delving into the history behind all the competing programmable consoles from this era, pulling together all the sources I could possibly find for each one. Topping it all off, we have an interview with Larry Wagner, the author of Combat and Video Chess (and the first head of Atari’s consumer development team for the VCS), a foreword by top-notch writer and my dear friend Jenn Frank, and absolutely lovely photography taken by Jeremy Parish of all the game boxes and cartridges – both the Atari and the Sears versions – as well as the consoles, the console boxes where i could source them, and some incredible rarities provided by other collectors. Rounding out the package are a slew of screenshots, flyer images, documentation and news clips where I could get reprinting permission. I can’t guess the amount of time I put into this book, and I am really thrilled with how it came out.

Of course, with Twitter’s rapid demise it’s been difficult to promote it, and frankly I’ve been bad about pushing it as much as I really should be. But if you or someone you know is interested in the history of Atari or early video games in general, I think this is the book for you. My goal was to provide as definitive an overview of these games and this era as I could, and I’m confident enough to call it one of the best books on Atari and that time period of video games out there. You can buy it directly from the publisher, Limited Run Games, and on Amazon. And hey, if you don’t want to go through those, why not ask your local book store to stock it too?

Entitled Atari Archive Vol. 1: 1977-1978, this covers the first two years of the Atari VCS’s life… and then some. If you’ve seen the video series or read this blog, you can guess the format of the book – much of it consists of delving into the history behind each game released in that two-year stint. The chapters are derived from these blog posts, but they aren’t identical, as I was able to come across some details during the writing of this book that I didn’t have putting the blog together.

Entitled Atari Archive Vol. 1: 1977-1978, this covers the first two years of the Atari VCS’s life… and then some. If you’ve seen the video series or read this blog, you can guess the format of the book – much of it consists of delving into the history behind each game released in that two-year stint. The chapters are derived from these blog posts, but they aren’t identical, as I was able to come across some details during the writing of this book that I didn’t have putting the blog together.